(From

www.chickasawhistory.com )

(From

www.chickasawhistory.com )

Home Page

10 April 2006

BIOGRAPHIES

Bio A-G

If a person has

a Lenape name, the biography is generally under that name. In any event, it

is cross-referenced with the English name. We have not yet fully decided on

whether to use the Lenape name of the English name as the primary name for

reference. Our preference is for the Lenape name, but that is not always

known by the person seeking information.

ADAMS, William H. - The Lenape name for William H. Adams is not known, but the English translation was Shooting Star. His later Lenape name was Walehohpseek. William Adams (Delaware Register #971) was born 13 or 15 September 1835 on the Verdigris River, north of the Clamore Mound, in Oklahoma. He died 29 August 1902 and was buried at Chelsea, Nowata County, Oklahoma. William recorded under oath to the Department of Interior that he was the son of Nancy Conner and Musetutsese. Nancy was the daughter of Indiana pioneer William Conner, a white man), and Mekinges, also recorded as Elizabeth Ketchum, a Delaware of the Turtle Clan. Mekinges left Indiana with the was Delaware Tribe some time in the 1820s, eventually to Missouri and finally to Kansas. Her death is unknown, but according to Karen Lynn, she may have survived as late as 1871. Nancy (Conner) Adams died in 1833 or 1834 in Kansas. Musetutsese was a Delaware from Missouri whose father was Paymarhting.

Family records say that Adam's first name was Shooting Star (Lenape name not known), because his father saw a meteor shower while on a hunting trip shortly before he was born. His teachers at the Shawnee Methodist Mission School changed his name to William Adams when he was a student there between January 1841 until January 1847. (Roger Berg, Jr., compiler, Listing of Students Enrolled in the Shawnee Methodist Mission). Adams family records indicate that the Adams' name began there. That is, the family had no connection to the presidential Adams. William Adams is on the Kansas Roll of Delaware who chose to remain in Kansas in 1867 with Allotment #77, but he later changed his mind and moved to Indian Territory (Oklahoma).

William Adams was enrolled as an adopted Delaware of the Cherokee Nation in compliance with the agreement made between the Cherokee and Delaware on 8 April 1867. All of his children were on the Cherokee Roll by 1896. William was a skilled carpenter. He built his own home in Nowata, Oklahoma and a number of other houses, including the home of Charles Journeycake and in 1877 the Bullettes' house in Claremore, Oklahoma. He also made the pews for the Delaware Baptist Church in Wingannon at which church he was later the pastor, replacing the ailing Reverend Charles Journeycake. William had earlier joined the Delaware Baptist Church on 12 June 1853 in Kansas, was licensed to preach the gospel on 1 February 186, and was ordained to the full work of the gospel on 14 March 1868. At one point he was a circuit rider preacher; his circuit Bible still exists. Many Delaware Council meetings were held at his home in Alluwe, Cooweescoowee District of Oklahoma in the late 1800s.

William H. Adams was married first

to Kate Woodfield (1840-1870) on 6 September 1863 at the Delaware Baptist

Mission Chapel in Wyandotte, County, Kansas by Reverend J. C. Pratt. She was

a white woman and a teacher who is believed to have started the first school in

Russell Creek, Indian Territory, south of Chetopa, Kansas.

Kate

was born in Indiana, died 24 October 1870, and was buried in the Russell

Creek Cemetery, Welch, Oklahoma. Their children are:

1.

Richard Calmit Adams (Dawes 54D, CS 52D) born 23 August 1864

at White Church Village, northeast of Piper, Kansas, died 4 October

1921, and was buried at Washington, D.C.

2.

Horace M. Adams (Dawes 55D, CS 53D) was

born 22 March 1866 at White Church Village [Kansas City],

Kansas, died 2 February 1949 in

Las Cruces, New Mexico,

and was buried in El Paso, Texas next to his younger

brother Judson Adams He was

married to Maud Branswell.

Horace Adams worked as an oil producer and prospector in Chelsea, Oklahoma. He and his

half-brother, Nathan Adams, bought a

ranch in

El Paso, Texas and

lived and worked there from 1908 to 1911. Horace was

responsible for doing much of the research work used by

his

brother Richard C. Adams in the books the latter wrote

about the Delaware Tribe.

3. Rosa E. Adams was born 23

November 1868 and died 4 October 1869.

William Adams

married second on 17 August 1873, Louise Zulkey of Douglas County, Kansas. They

were married at the home of John Sarcoxie by Reverend Charles

Journeycake, pastor of the Delaware Baptist Church. Louise was

born 6 September 1857 at Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the child of Charles and Christina _____

Adams. She died 25 June 1937. The family story is that after Louisa

[Louise] Zulkey and her brother Mark Zulkey were

orphaned as children when their parents were killed in a wagon accident,

they were taken in by John Sarcoxie. They learned to speak Delaware fluently

in his home. Several pieces of beadwork done by Louisa survive.

The children

of William and Louisa Zulkey Adams (family census card #10639, Dawes enrollment

#31559) are all on the 1896 Cherokee Roll. They are:

4.

Nathan Francis Adams

was born 6 December 1874 at Alluwe, Cooweescoowee District.

Cherokee Nation, I. T.,

died 17 September 1960,

and was buried at Gum

Springs Cemetery, Longview, Texas. He served a a U.S. Marshal

in Oklahoma before it became a state. He later moved

to El Paso where he and his brother

Horace in 1908

purchased the Crosby ranch in Cayanosa, Pecos County and ran it

for several years. Nathan

later worked as a

Special Officer for the Texas

and Pacific Railroad under the Texas Ranger forces. He married Effie May

Jackson

from

Claremore, I. T. in 1894. After her her death, he married

Wordy

Gladys Martin from Texas in 1919.

5. Clinton L. Adams, was born 7/8 February

1877 at Alluwe, I. T. , died 11 June 1899 in a railway accident, and is

buried at Chelsea, Oklahoma.

6.

Abner G. Adams was born on 30 April 1880 at Alluwe, I. T., and died

20 October 1946. He was married to

Jessie _______. They resided in Seattle,

Washington at the time of his death.

7. Nettie E. was born

2 November 1881 and died 26 July 1882. Her last known residence was at

Kansas City, Missouri.

8.

Lottie J. Adams

was born 27 April 1883 at Alluwe, I. T. She married first 20 May

1905 Charles Gillespy and

married second ______ Mertines.

9.

Judson H. Adams was born 22 March 1885 at Alluwe, I. T., died 19

September 1909, and was buried in El Paso, Texas, next to his older half-

brother,

Horace Adams

10.

Josephine R.

Adams was born 26 October 1887 and died 5 March 1977. She married in 1908

William

Vern French.

11. Hiram V. Adams was born 4 February

1891 at Alluwe, I. T. and died 1 January 1964 at Los Angeles California. He married first

Lucy

Milam from Alabama and

married second, Helen_______.

12.

Levi P. Adams was born at Alluwe, I. T. on 23 or 28 September 1893 and died 7 October

1894.

13. Reuben B. Adams was born 23 March 1896 at

Alluwe, Indian Territory and

died 25 January 1987 at Odessa, Texas, where he was buried in

the Sunset

Memorial Garden.. Reuben is on the

1906 Per Capita Roll for the

Delaware Tribe, Delaware Registration No.

31560. He worked in

Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas with Phillips

Petroleum. He

retired in Odessa and was living there when he died. Reuben married 1.

Hattie H. Oliver (1898- 1962). He married 2. Ruella

________ .

The children

of Reuben B. Adams and Hattie Oliver are:

(1) Mary Louise Adams Sears,

living.

(2) Reuben B. Adams, Jr. was born 28 October 1922, deceased.

(3)

Kenneth L. Adams was born 4 November 1924, deceased.

(4)

Norma Jean Adams,

living.

(5) Shirley Ann Adams Shepard, living.

Obituary: Kansas City Star,

Aug. 30,

1902. "Aged Indian Preacher Dies - The Rev. Mr. Adams of the

Indian

Territory Dead Here." The Rev. William Adams, a Baptist minister at

Alluwee,

I. T., died early this morning at St. Joseph's hospital of kidney disease. The

Rev. Mr. Adams was of Indian blood, his father having married into the Delaware

Tribe of Indians. He was a Baptist minister, and was pastor of a church of

Indians located in the Cherokee country. With his two sons he had been spending

his vacation in Minnesota, where he was suddenly stricken, while at St. Paul. An

operation was performed, and he was brought to Kansas City last night and taken

to St. Joseph's hospital, where he died this morning. The Rev. Mr. Adams leaves

a widow and three sons. two of who accompanied him on his trip. His son, H. M.

Adams, an attorney at Washington, D.C., for the Delaware Indians, arrived last

night and was with his father when death came. The body was sent to Chelsea, I.

T., today for burial. The Rev. Mr. Adams was 72 years old. (He actually had

three sons living at this date. Richard was the attorney in Washington,

D.C.)

(Researcher: Karen Lynn. William H. Adams is her great-great-grandfather. Data has also been provided

by Russell Sears, a great-grandson of William H. Adams. russell.sears@gcmail.maricopa.edu

* Ruby Cranor in "Kik Tha We Nund" the Delaware Chief Anderson, p. 124, states, "William Adams the second son of John Quincy Adams and Nancy Conner Adams was born in 1852. He was given the name of Walleoakse." Researcher Karen Lynn says that family records show no relationship to the earlier Adam's family. Lynn also notes that she [Ruby Cranor] has recorded the largest collection of information about the Adam's pedigrees. See the Bibliography for the details of Ruby Cranor's her book. In her book, Some Old Delaware Cemeteries, p13, Ruby Cranor includes this item concerning him:

William A. Adams (Wa Le Oak Se), a half-breed Delaware was born in the early 1830's on the Delaware Reservation in Kansas. He was married twice and had 11 children. He was a lawyer and did a lot for the Delaware tribe. He lived in Washington D.C. where his younger children were born. We do not have any record of his death except from the family bible. This bible now belongs to Josephine Adams of Nowata. It says Mr. Adams died on the 29th of August 1902.

Researcher Karen Lynn notes: Most of the information I am sharing I obtained from family records by Nathan Francis Adams, an older brother of my great grandfather, Hiram V. Adams. I am unable at this time to find out if his [William Adam's] grandmother, Mekinges, was involved in his upbringing or whether his uncles, Chief John Conner or James Conner, were involved with his upbringing during his childhood.

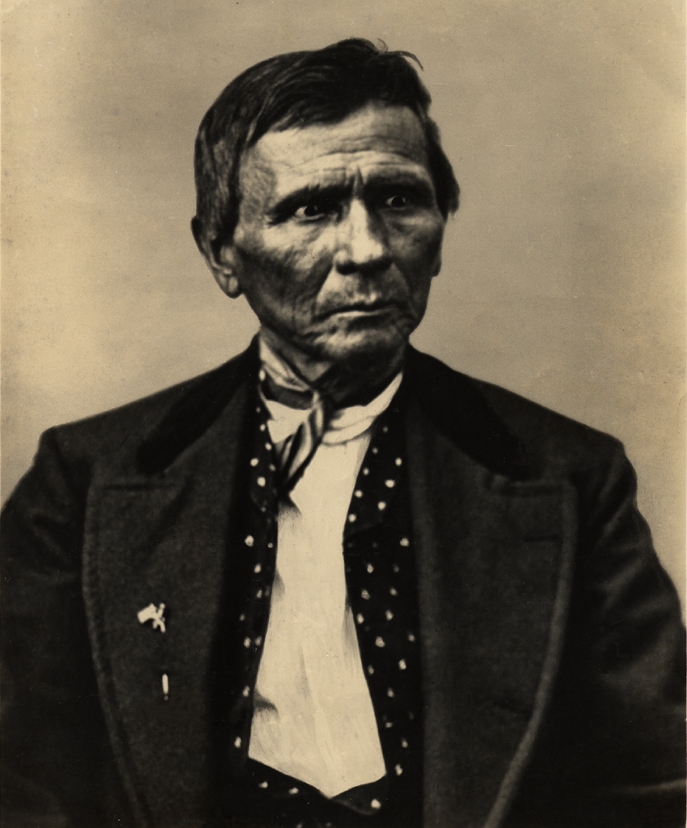

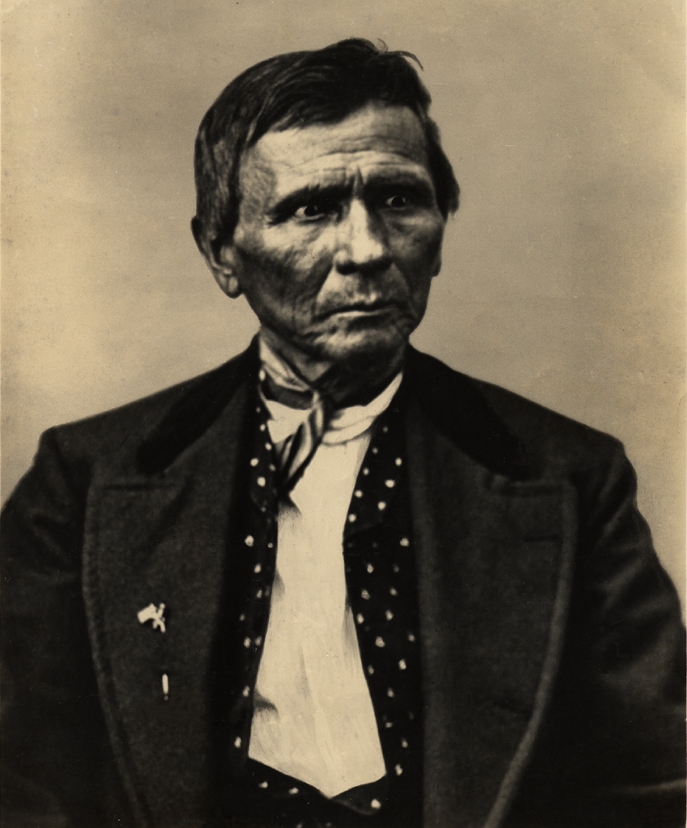

William Adams is in a photograph of a group of Delaware who went from Kansas to Indian Territory.

Researcher: Karen Lynn said in December 2000, "Most of the information I am sharing I obtained from family records kept by Nathan Francis Adams, an older brother of my great grandfather, Hiram V. Adams . . . I believe [William Adams] to have been an honorable man who was very active in the Delaware Tribe during his life. Ruby Cranor in Kik Tha We Nund: The Delaware Chief William Anderson and His Descendants, described him as a man that embraced the white man's way. I describe him as a man that lost his mother when he was one or two years old living in questionable circumstances in Kansas during a time when the Delaware Indians were pressured (once again) to move on....I do not know when his father died or the circumstances of his father's life....As I understand these time historically and culturally, Indian children were not allowed to use their true native names nor were they allowed to wear their native clothing. I believe that William Adams was partially influenced by times and circumstances that did not encourage or really allow Indians to exist as individual people."

ADAMS, Richard Calmit--Richard Calmit Adams (Dawes 54D, CS 52D) born 2 August 1864 in White Church Village, northeast of Piper, Kansas, died 4 October 1921, and was buried at Washington, D.C. He married Carrie F. Meggs. Richard was a minister and served as a Representative of the Delaware in Washington until the time of his death. Richard was an activist for the Delaware Tribe, often without financial reimbursement. He was a great orator and historian and authored several books, including A Brief History of the Delaware Indians. Richard Calmit Adams was an activist for the Delaware. He worked passionately in defense of the tribe, often without financial reimbursement in pursuit of legal matters in Washington, D.C. Richard Adams, John Bullette, William Adams, and possibly Horace Adams owned a coal mine near Chelsea, Oklahoma.

Obituary. From

a local newspaper of Longview, Texas, where Richard's younger brother,

Nathan P.

Adams, lived: Hon. Richard C. Adams.

N. F. Adams, chief special officer for the

Texas & Pacific Railway in the Marshall shops received news this morning of

the death of his brother, Hon. Richard C. Adams in Washington, D.C., on

the night of October 4, 1921. Richard C. Adams was one of the well known

representatives of the Indians in Washington and went to Washington many years

ago before Oklahoma was a state, where he became the representative of the

Delaware Indians. It was due to his efforts that the Delaware Indians received

their equal rights with the Cherokee Indians which was won in a suit in land and

money. Mr. Adams spent the last 24 years of his life at the national capitol, in

the New Ebbitt house, fighting for the rights of the Delaware Indians. The

deceased is survived by his wife and several children and his brother N. F.

Adams, here and a sister in Nowata, Okla. (There were also his mother, Louisa

Adams, three other brothers and another sister at the time of his death. There

is also a poem entitled "A Tribesman's Departure" that is not included

herein.)

A photograph of Richard Adams with a group of Delaware who went from Kansas to

Indian Territory can be found at the bottom of the Home Page.

ANDERSON, Arthur--"The funeral of Arthur Anderson, aged Delaware pioneer of Washington county [Oklahoma], was held yesterday afternoon at the Baptist church. Rev. J. B. Rounds of Oklahoma City conducted the service. Members of the Delaware Indian Tribe had charge of the services and an Indian funeral ceremony was preached. Tribal songs were sung and members of the G. A. R. attended the services. Mr. Armstrong was a charter member of the local post and saw service during the Civil War with a Kansas regiment of infantry. Burial was in the mausoleum of the White Rose Cemetery. Arthur Armstrong figured in the history of the making of Bartlesville. He was born in 1848 on the Wyandotte Kansas reservation and was of French and Delaware blood. He came to Indian Territory with the Delawares when moved here by the government. He served with the 6th Kansas Calvary during the Civil War and made three trips to Ft. Douglas, Utah with supplies by ox team. His allotment of 160 acres was in the northeast section of what is now Bartlesville and his old home at the end of North Seneca Avenue still stands. Mr. Armstrong was a devoted Baptist and a great admirer of Chief Journeycake and he erected the first building in Bartlesville to be used as a church and school. Supplies for this building were hauled from Baxter Springs, Kansas. He was married three times. His first wife was Nancy Ketchum, mother of Henry Armstrong. She was a daughter of Chief John Ketchum and was a full blood Delaware. His second wife was a daughter of Col. Jackson, a Delaware, and his third wife, Maggie Davis, who survives, was a white woman. His son, Henry Armstrong and five grandchildren survive also. (Bartlesville Examiner, 21 November 1919 in Ruby Cranor's Some Old Delaware Obituaries. See the Bibliography for ordering information.

ANDERSON, William--See Kikthawenund.

AUPAHMUNDAGEOCKWE or AQUAMDAGEOCKWE

-

See Ketchum, Nancy

AUPHEEHELIQUA

- See Ketchum, Nancy [2]

ANDERSON, William Henry--See Windsettund.

BLACK

BEAVER -

(From

www.chickasawhistory.com )

(From

www.chickasawhistory.com )

Black Beaver. A Delaware guide, born at the present site of Belleville, Ill., in 1806; died at Anadarko, Oklahoma, May 8, 1880. He was present as interpreter at the earliest conference with the Comanche, Kiowa, and Wichita tribes, held by Col. Richard Dodge on upper Red River in 1834, and from then until the close of his days his services were constantly required by the Government and were invaluable to military and scientific explorers of the plains and the Rocky Mountains. In nearly every one of the early transcontinental expeditions he was the most intelligent and most trusted guide and scout. (Ancestry.com)

The following is an article on Black Beaver from The Anadarko Daily News of 5 and 6 August 2000 entitled, "Black Beaver Set a Good Example."

The Delaware Indians have always claimed to be the grandfathers of all other red men, and they are proud of the fact that they signed first treaty with William Penn. There is another fact that qualifies them in feeling superior, and that is that Black Beaver was a member of their tribe. This Indian who served the United States so faithfully helped to bring fame to several army officers and explorers who were fortunate to have him for a guide. He set a good example to his own people by the manner in which he conducted his affairs and the home he maintained. [As though other Delaware did not?! Editor].

It is probable that some members of the Delaware tribe were on their way west to make their home when Black Beaver was born at the present site of Belleville, Illinois in 1806.

When the Delawares were being removed and located on [the] White River in Arkansas they were left in a desperate state because white people stole almost all of their horses. In February, 1824, William Anderson, the head chief, Black Beaver, Natacoming and other Delawares sent a touching letter to General William Clark regarding their conditions.

Last summer a number of our people died for just for the want of something to live on ... We have got in a country where we do not find all as stated to us when we was asked to swap lands with you ... Father ... You know it is hard to go hungry, if you do not know it we poor Indians know it ... We are obliged to call on you once more for assistance in the name of God. ...

When Black Beaver was twenty-eight years of age he acted as interpreter he acted as interpreter for Colonel Richard Irvings Dodge at his conference with the Comanche, Kiowa and Wichita in 1834 on [the] upper Red River. Dodge wrote of him and his people: Of all the Indians, the Delawares seem to be the most addicted to these solitary wanderings, undertaken, in their case at least, from pure curiosity and love of adventure. Black Beaver, the friend and guide of General (then Captain) Marcy, was almost equally renowned for his wonderful journeys." Dodge was comparing Black Beaver with "John Conner head chief of the Delawares who was justly renowned as having a more minute and extensive personal knowledge of the North American continent than any had or probably will have."

In the celebrated Dragoon expedition of 1834, commanded by General Henry Leavenworth, there were thirty-two Indians, including six Delawares, among whom was Black Beaver, and from that time he was in almost constant demand as a guide and interpreter. In 1846, during the war with Mexico, a company of Delaware and thirty-five Shawnee Indians under Captain Black Beaver were mustered into the service on June 1, and discharged in August, although their time did not expire until December.When Captain Randolph B. Marcy left Fort Smith on April 4, 1849, to escort five hundred emigrants to California, he was ordered to select the best route from the Arkansas town to Santa Fe and California. At Shawneetown where the road forked, the left being his trail, he engaged Black Beaver as guide and interpreter, and he proved to be a most useful man

He has traveled a great deal among the western and northern tribes of Indians, is well acquainted with their character and habits, and converses fluently with the Comanche and most of the other prairie tribes. He has spent five years in Oregon and California, two years among the Crow and Black Feet Indians. He has trapped beaver in the Gila, the Columbia, the Rio Grande, and the Pecos. He has crossed the Rocky Mountains at many different points and indeed is one of those men who are seldom met with except in the mountains

Captain Marcy became a noted pathfinder in the Southwest and much of his success was due to Black Beaver, upon whom he relied. Jesse Chisholm, Black Beaver, and other guides had been to California at at early date and they were regard with respect and their advice adopted regarding routes to the far West.

The grace and rapidity with which Black Beaver carried on conversations with Indians of other tribes astonished Marcy. This was done by pantomime and the Captain wrote that their facile postures would compare with the most accomplished performances of opera stars.

On the return trip Black Beaver was confident that he could lead the party from [the] Brazos River to Fort Smith, so the force took a course directly across the country, "making a most excellent road, which was traveled for several years afterward by California emigrants."

In 1852 Lt. A. W. Whipple had been informed that Black Beaver (Si-ki-to-ker) never forgot a place that he had seen even if many years had passed and if their horses strayed the Delawares could always find them

When the expedition arrived at Fort Arbuckle some of the men visited the log house of Black Beaver, where "under a single corridor, on a rough wooden settle, an Indian sat cross-legged smoking his pipe, and awaiting his visitors in perfect tranquility. He was a meager-looking man of middle size, and his long black hair framed in a face that was clever, but which bore a melancholy expression of sickness and sorrow, though more than forty winters could have passed over it.

The arrival of visitors did not seem at all to disturb him, and his easy and unembarrassed manner showed that he was quite accustomed to speaking with whites. He spoke fluent English, French and Spanish and about eight Indian languages. A tempting offer was made to Black Beaver and immediately his eyes sparkled with their old fire, but he sadly replied:

Several times I have seen the Pacific Ocean at various points and have accompanied the Americans in three wars and I have brought home more scalps from my hunting expeditions than one of you could lif. I should like to see the salt water for the eighth time; But I am sick--you offer me more money than has ever been offered before--but I am sick...but if I die I should like to be buried by my own people."

No inducement could make him change his mind and the explorers decided that the idea that he might die on the way suggested to him by his wife who objected to his going. For three days the white men attempted to get Black Beaver away from the determination of the woman but at night she was able to counteract their influence, and all they got was advice from the canny guide.

From the Brazos Agency, Texas, on August 31, 1855, Special Agent G. W. Hill reported to R.S. Neighbors, special and supervising agent. that in obedience to his instructions in March, 1855, he had settled on the reservation seven hundred and ninety-two Indians. He also wrote that recent runners from the north of [the[ Red River reported that [the] Wichita chief informed him that through Black Beaver, guide and interpreter, at Fort Arbuckle, that arrangements were making to settle about two hundred Indians of four tribes there with the Wichitas.

The Delaware and Caddo Indians lived with the Wichitas at the time when they were permitted to select land in the Leased District for a new home on the north side of the Washita on Sugar Tree Creek. Matthew Leper, the new agent, made his first report September 26, 1860, and the description of the new home of Black Beaver shows the Indian to have been far in advance of his neighbors.

The best improvement found on the preserve is a private enterprise of Black Beaver, a Delaware Indian located here. He has a pretty good double log house, which two shed rooms in [the] rear, a porch in front and two fireplaces, and a field of forty-one and a half acres enclosed with good stake-and-rider fence, thirty-six and a half of which have been cultivated

When the Medicine Lodge Peace Council was held in the autumn of 1867, many prominent army officer4s, Indian agents, newspaper correspondents, and Indians were present. This council was called in an attempt to settle a war which had gone on for three years and was brought on by the Chivington massacre in Colorado. Black Beaver, then sixty-one years old, was present among many other noted Indians.

Colonel William B. Hazen of the agency had two hundred acres plowed in the Washita valley for thirty Delaware Indians belonging to his agency, and Agent Tatum had the tract fenced. Black Beaver was the only member of his tribe who settled near the field, and as other Indians preferred to farm near the timber he wished to cultivate he whole tract, but Tatum thought it would be too much for him and he engaged a white man to farm forty acres on shares with the government. When he inspected the field in the he found that the white tenant had raised as many weeds on his part as Black Beaver had on the one hundred sixty acres he farmed. Tatum agreed to allow the Delaware to farm the whole acreage the following year. "He was a successful farmer, respected by all the Indians who knew him, and his influence with them was always good. He was a Christian, and tried to do what was right in the sight of God and towards his fellow-men."

Black Beaver built the first house at Anadarko; it was near the Washita and a short distance west of the Indian agency. When Pat Bruner went to Anadarko in 1871, he married Beaver's daughter, Mrs. Osborne, after her husband's tragic death. Jesse Sturm, a son of J. J. Sturm, married Mrs. Osborn's daughter Marie.

In October, 1872, Captain Henry E. Alvord, special Indian commissioner, took a part of Plains Indians to Washington and New York. The delegation comprised Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Arapaho, Caddo, Wichita, Waco, Kichai, Tawacearo, and Delaware; the latter tribe was represented by Black Beaver.

According to the New York Herald, October 31, 1872, "The red men [were] on a tour to learn Fraternity and Christian Virtues." They lodged at the Grand Grand Central Hotel and Black Beaver was introduced as a former guide to Audubon.

In 1872, when Black Beaver was sixty-four years of age and too feeble to work for his living, he filed a claim with the government for the value of his property on the Washita river abandoned in the spring of 1861 and subsequently destroyed by the Confederacy. Payment had been promised him by Major Emory, Captain Delos B. Sacket and Lieutenant D. E. Stanley. The committee on Indian Affairs recommended only $5,000. less than a fourth of Black Beaver's claim.In a letter written by Israel G. Vore about 1879 he said:

Black Beaver will soon be 71 years old and has spent the greater portion of his life in the service of the officers of the United States civil and military. He served the United States under General s Honey, Marcy, Belknap, Emory Sacket, and Stanley and various other officers and Agents and Superintendents of Indian Affairs, as guide and interpreter--none of whom ever charged him with falsehood, or a dishonorable act."

Agent P. H. Hunt from Anadarko, on August 30, 1879, singled out Black Beaver as a prosperous citizen in his report: " Black Beaver, a Delaware, has 300 acres of land enclosed and fully cultivated and is the possessor of considerable stock, hogs, cattle, and horses."

In later life Black Beaver became a Baptist minister. As a farmer he always set a fine example to his tribesmen and other Indians. The late Mr. E. B. Johnson of Norman, Oklahoma, wrote to Grant Foreman regarding the Delaware:

..... I knew Black Beaver well--He was typically named as he was an unusually dark Indian--often came to Fether's on his journeys and said he was with Jesse Chisholm when he died--[he] lived among the Cado when they lived in what is now know an Paul's Valley--most of them lived in grass houses or teepees and when they were moved out to Sugar Creek he went with them, but often returned for his usual visit

On June 2, 1889, from the office of the Kiowa, Comanche & Wichita Agency, Anadarko, Indian Territory, Agent P. B. Hunt wrote to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington:

.... On the 8th day of May, Black Beaver, a Delaware, and the most prominent of all the Indians belonging to the old Wichita Agency, died suddenly of heart disease, in the 72nd [74th] year of his age. He was many years ago a noted guide and acted in that capacity for Fremont, Auderbon [sic] and Marcy; had acquired a fair knowledge of English & delighted in speaking it, when occasion offered; was a good friend of the white man, had professed religion. had consented to two of his daughters marrying white men, & set his red brethern [sic] a good example by his untiring industry & earnest desire to follow the white man's road to the end. [A doubtful honor. Editor]

His burial took place the day following his death, and more 150 persons showed the esteem in which he was held, by following the remains to their last earthly resting place. The coffin was borne Agency employees and other white residents and burial services were conducted by Delawares led by their Seminole preacher.

Black Beaver's grave, about half a mile west of the agency and a short distance southwest of his farm, is protected by the United States in a small reservation.

Members of the Oklahoma State Historical Society, in its annual meeting at Chickasha in April, 1937, visited Black Beaver's grave and several other places closely associated with the celebrated Delaware.

Editor's Note: In 1976 Black Beaver's grave was moved to Fort Sill near Lawton and placed on the Chief's Knoll. A bust of Black Beaver is in the National Hall of Fame for Famous Indians, in Anadarko.

The following items are from Richard C. Adam's, Delaware Indians: A Brief History:

The saying is true that "the blood of the soldier makes the general great." It is the conscientious discharge of duty by the subordinates of an army, stating the principal more broadly, "that makes the efficient army." Black Beaver, the famous Delaware scout, is a most satisfactory example illustrative of this. His character, modest, faithful, conscientious in the discharge of every duty, and seemingly oblivious of any personal danger, places him on an exceeding high plane, worthy of imitation. He had the absolute confidence of those that he guided from danger to safety. He never served anyone that did not bear testimony to his zealous discharge of his duties. The following is a letter from Black Beaver to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs:

DEAR SIR: I take the liberty of addressing my grievances to you and of respectfully asking your advice in a matter in which I am earnestly concerned,

I would represent that I am an Indian, belonging to the Delaware tribe, that I have been in the employ of the Government all, or nearly all, the time since the commencement of the Mexican was. During the Mexican war I was captain of a company of Shawnee and Delawares in the United States Army.

Since that time, up to the commencement of the last war, I have been employed as a guide or interpreter by the different commanding officers at the posts of Arbuckle and Fort Cobb, in the Indian Territory, and by superintendent and agents for the Indians in the vicinity of Fort Cobb and Arbuckle, as can be attested by General Marcy, Emory, Sturgis, Stanley, and Sacklitt, any or all of the military officers stationed at the aforementioned posts prior to the war, as also ex-Superintendent Rector, of Arkansas, and all of the United States Indian agents in that locality.

I was at the post of Fort Arbuckle for about five years and the post of Fort Cobb one year immediately preceding the last war, and during that time had invested all of my means and earnings in cattle and hogs, and had, at the breaking out of the war. a large stock of cattle and hogs, as will be attested by some, if not all, of the aforementioned persons.

In the spring of 1861 General Emory requested me to guide his command and also the combined commands from Fort Smith, Cobb, and Arbuckle to Fort Leavenworth, Kans., which I did, but hesitated about leaving my stock until General Emory assured me that I should be paid by the United States for my losses; and on that representation I complied with his request and came with his command to Fort Leavenworth, Kans., and remained here until the war ceased, when I visited my old place and found that my stock was killed, some having been destroyed by the wild Indians and some by the Southern army.

About two years since I acquainted United States Indian Agent Shanklin with the facts and asked him to adopt measures for procuring my pay for me. He was agent for the Affiliated Bands of Indians in the southern superintendency, and I was at the time employed as interpreter under his direction.

I have had no word from him in the matter and do not know whether he made any effort in my behalf or not.

I therefore make this request at your hands, hoping that if it may not be in your power to give attention to such matters that you will advise me as to the best course to pursue to get my dues.

I am now an old man (upward of 60 years old) and too feeble to earn a livelihood, and what is justly due me from the Government is all that I have to depend on in my old age. Most, if not all, of the officers before named are well acquainted with me and can vouch for the correctness of my statements.

As to the extent and nature of my claim, I can furnish abundant proof, as many persons of my acquaintance before the war at at their old places.

I would respectfully ask that you make inquiry of General Marcy or General Emory as to my character and claim, and that you would advise me as to the best course to pursue in the premises.

I have never realized 1 cent from the property that I abandoned, and am now in need.

I do not think that Agent Shanklin has made any effort whatever on my behalf, or if he has, it has been done in such an indirect manner that he has either accomplished nothing or has failed to advise me of the result.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, BLACK BEAVER, Address box 22, Baxter Springs, Kans.

The COMMISSIONER OF INDIAN AFFAIRS Washington, D. C.

Gen. W. H. Emory wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in reference to Black Beaver as follows:

WASHINGTON, JUNE 12, 1869.

GENERAL: I have read carefully the letter of Black Beaver, the Delaware guide, dated Baxter Springs, Kans., June 3, 1869, and I hereby certify that it is every word true. And I exceedingly regret that the Government has so far neglected the claim of this worthy and patriotic man who has rendered such eminent and valuable service.

When the war broke out I was in quasi command of the troops in the Indian country in the northern part of Texas that is to say, I was to take command and withdraw the troops only in case Arkansas passed the act of secession. She never passed that act before proceeding to actual hostilities and to the attempt to capture the troops stationed in the Indian country, so that when I got information of what was going on I was obliged to act without orders from the Government. Orders subsequently arrived, but not until long after the steps were taken which I now describe and in which Black Beaver rendered such splendid service.

That step was to concentrate all the troops at Arbuckle and withdraw them en masse. Before the concentration could be effected, I learned from undoubted authority that 4,000 rebels from Texas were marching directly on me and that some 2,000 from Arkansas were moving to strike my flank

This compelled me to seek, with my comparatively small command, the open prairie. To do this guides were essential, and, of all the Indians that the Government had been lavishing its bounty, Black Beaver was the only one that would consent to guide my column.

He was living near Fort Arbuckle, in a comfortable house, surrounded by his family, with a small [farm] fairly well stocked with cattle and horses and a field of corn. All these he abandoned to serve the United States, with a full knowledge that in doing so his horses and cattle would be seized by the enemy, and his property destroyed, and such was the case, and Black Beaver has never returned to his home, and it is my belief, if he was now to return he would be murdered by the bad white ment who in 1861 instigated the Indians to go into rebellion against the United States and whom he so greatly offended by guiding my command through the prairie in safety to Fort Leavenworth.

I need not say how invaluable was his service and great his sacrifice on that occasion. He was the first to warn me of the approach of the enemy and give me the information by which I was enabled to capture the enemy's advance guard, the first prisoners captured in the war.

I can not too urgently press upon the honorable Commissioner the justice of this claim and the pressing necessity there is for doing something at once to relieve the wants of this aged and worthy man.

I have the honor to be yours respectfully. W. H. EMORY Brevet Major-General, U.S. Army.

Gen. E. S. Parker, Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

I estimate Black Beaver's loss at about $5,000. W. H. EMORY

W. H. Emory, whose heart indorsement of the long delayed and eminently just claim of Black Beaver against the United States does him credit, was abreast of our foremost army officers in conspicuous and efficient service for many years. He felt when he penned that letter that his friend Beaver deserved well of the Reopublic, and no doubt greatly regretted the Government's neglect. He comprehended to its fullest extent the value, at personal sacrifice, of the service rendered his soldiers (and himself) in extracating them from very serious danger. If the Confederates had succeeded in capturing his command, their prestige would have greatly increased and the Federal cause proportionately injured. We can not now measure the value of the services of the veteran scout, but if disaster had befallen General Emory, several chapters relating to the civil war would have been differently written.

Gravestone in Fort Sill Cemetery, Oklahoma (From

www.accessgenealogy.com )

Gravestone in Fort Sill Cemetery, Oklahoma (From

www.accessgenealogy.com )

CALEB, Sabilla

- Entry being

entered this date. Sabilla went to present Kansas with a search party to

negotiate with the Delaware (and later the Chippewa) regarding the Munsee move from

Wisconsin to present Kansas. She married first and second

Munsee Noah Nathan in Wisconsin. She

then married Tom Eliott/Elliott, and then Reazin/Rezin

Wilcoxen/Wilcoxon, probably in Leavenworth County Kansas. The year of

their marriage has not been proven. Two years that we have come across are 1851

and 1854. The year 1854 is probably more realistic. It appears that Rezin had

been previously married to Melinda Statler. Rezin and Sabilla's child was Josephine Wilcoxon

(as she spelled it in her

own handwriting), born in 1852 in Leavenworth County. The Munsee, who had

moved from Wisconsin to Leavenworth County about 1836, moved

to present Franklin County, Kansas about 1859. Josephine moved to

Franklin County at the age of seven, that is, about 1859.

Apparently she was with her mother, Sabilla, but it appears that her father

remained behind as was married to Melinda Wilcoxen by this time. She first

married Munsee, or Chippewa, Moses Kilbuck at the age of 14, and later married John William

Plake.

(Much of the data on this entry was provided by Researcher Linda Plake Sparlin

lsparlin@rollanet.org . Linda is the

great-great-grand daughter of Rezin Wilcoxen and Sabilla Caleb and the great

grand daughter of John William Plake.)

COMPSTON, Ella Eliza - She is listed under Sarah Halfmoon

William Conner and Elizabeth Conner

By Timothy Crumrin

When early ethnographer and linguist C. C. Trowbridge entered Indiana during the late autumn of 1823 he was very much a man on a mission. Trowbridge had been charged by Lewis Cass, Governor of the Michigan Territory, with making scholarly enquiries into the life ways and language of the Delaware Indians. On December 5th, "after a tedious and rather unpleasant journey" through the state, he finally reached the White River home of a man who could help him with his study. Trowbridge found William Conner "a good deal employed in necessary attention to his business," but anxious to help the earnest young scholar. Conner's wide experience among the Delaware and other Native Americans made him an ideal resource. Indeed, for most of his forty-six years he had performed a precarious balancing act between two worlds: Red and White. He spoke the words of both worlds, lived and dressed as both did. He continually walked the knife-edged path dividing the two divergent cultures, never, seemingly, wholly a part of either. As a result, he had intimate knowledge of both societies-- and how they interacted with one another.

Ironically, Trowbridge also found Conner overseeing the completion of the most concrete affirmation of his desire to step away from that narrowing path, his new home. Conner's two story brick house was his signal that he had crossed the line, the symbol of his full entrance into white society. It was at once the completion of one journey and the first step upon another. William Conner was born onto the tightrope; his first steps pointed him toward a trail already blazed by his family. In many ways it was a quintessentially American story, one abounding in the icons of the American consciousness: Indians, pioneers, and the foreboding frontier.

William Conner's birthplace was on the frontier's jagged edge that was Ohio in 1777--probably in Lichtenau. His father, Richard, a sometime trader, sometime tavern keeper, had spent most of his life moving from one wilderness to another. As historians John Larson and David Vanderstel noted, Richard Conner's life adumbrated his son's and provided a possible framework within which to live it.

Born in 1718, Richard Conner [C.] left his native Maryland to roam the forests of western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio in search of furs. At some point he encountered Margaret Boyer, a white woman raised in Indian villages after her capture by the Shawnee. Ransoming her for $200 and a promise to turn over their first-born son, the fifty-something Richard married Margaret and lived among the Shawnee. Their son James, born in 1771, was dutifully given to the Shawnee. It was a rugged existence, but one for which Conner, described by a missionary as one who feared neither man nor God, and his family seemed well suited. In 1775 the family was uprooted from the Shawnee village where Conner kept a tavern by the ongoing conflicts which characterized the frontier. After ransoming James, they threw in their collective lot with the Moravian missionaries and their Delaware converts who founded Schoenbrunn, Ohio. The Moravians, a Protestant sect which proselytized among Native Americans, gathered their converts into mission towns normally closed to outsiders. For reasons which remain unclear, an exception was made for the Conner's who were to follow them to Lichtenau. This world on the fringe presaged the one in which William Conner would inhabit for much of his life.

Caught in the crossfire of the Revolutionary War, the Conner's joined the Delaware and the missionaries on their British-forced removal to Michigan, exchanging one unsettled area for another. The arrival of peace brought the departure of the Moravians and their followers, who returned to Ohio. Richard Conner, now in his sixties, decided to remain. Eventually purchasing over 4,000 acres of land in what became Macomb County, he established a trading post and became a facilitator of settlement. Although he acquired land from his father, William also inherited his sense of wanderlust combined with a trader's instincts. By 1795 William was trading with the Native Americans around Saginaw Bay.

William and his older brother John arrived in Indiana during the winter of 1800-1801 as agents for a Canadian fur trader named Angus Mackintosh. To anyone else it might have been a daunting and foreboding venture, but to the Conner Brothers it must have seemed the reawakening of a vestigial memory. Once again they were beyond white settlement, living and trading among Native Americans. Both men settled among the Delaware, who lived in villages strung along the White River from north of present day Indianapolis to modern Muncie. Both married Delaware women; according to legend, William's wife, Mekinges, was the daughter of Chief Anderson, but no concrete evidence supports this claim. Traders often found it to their advantage to marry into the tribes with which they dealt. It eased their way into the community and helped assure a feeling of loyalty. As in the case of William Conner, it increased their influence and allowed the trader to exert some control over the actions of the tribe. Traders often became unofficial liaison officers between the "their Indians" and the white world and government.

William Conner soon attached himself to the land which now bears his name. The 200 acre prairie, hard by the White River, was an ideal location for both agriculture and trade. He built a log home which doubled as a trading post and with Mekinges began raising a family. John Conner moved closer to settlement by relocating to the Whitewater Valley area (where he was to later plat Connersville) in 1803. From there he acted as a middleman, marketing the peltry sent by William and returning trade goods and liquor for his brother's Indian customers. Officially licensed traders since 1801, the brothers' activities made them a part of a complex economic network well on its way to eroding many aspects of Native American life and culture. An old pattern in which newcomers first came looking for the bounty of the land and then cast covetous eyes toward the land itself was being retraced in Indiana. The dependence engendered by the trade allowed the government to manipulate and coerce tribes into ceding their homelands. The Conners were to have small but vital roles in the process.

John Conner was the first to add another layer to the liaison role by officially performing duties for the government. Venturing forth from his "civilized" area once more into the wilds, he served in several capacities under William Henry Harrison and others beginning in 1808. William appears to have eschewed any official role prior to 1811, but increasing conflict and the War of 1812 drew him into government service. The man who had lived and worked with Native Americans most of his life, who had married a Delaware woman, whose children were certainly more "Indian" than "American," became a soldier, scout, interpreter and spy for those who were arguably his family's enemies. Among the services rendered by William Conner were maintaining Delaware loyalty during the war and identifying the body of Tecumseh following the Battle of the Thames, the defeat which essentially sealed the fate of Native Americans east of the Mississippi.

All the while Conner continued his trading and farming activities. His home on the White River became a gathering place for Native Americans and a stopover for the few white travelers. His family continued to grow. He and a partner, William Marshall, accrued profits not only from their regular trading, but from the extra income provided by land cession treaties--Conner had been a part of eight such negotiations-- and their aftermath. William Conner's roles as interpreter and liaison at the Treaty of St. Mary's in 1818, in which the Delaware ceded lands in central Indiana for those west of the Mississippi, were a continuation of his efforts over the decade. At the back of his mind he must have been aware that his participation would lead to a drastic, almost organic, alteration of his life. Changes wrought in the Delaware world were changes wrought in his.

Conner worked in the background as something of a fixer. He helped assess what it would take to get the tribes to accept the inevitable treaty. He helped "sell" the treaty to Anderson and the other chiefs by pointing out its benefits and arranging bribes and under-the-table payments to Delaware leaders. Conner earned profits from the removal by arranging to provide supplies for the trek. With the signing of the treaty the days of the Delaware--and Conner's family--in Indiana were numbered.

The Delaware gathered-- ironically, they were preceded by the commission charged with selecting a site for Indiana's new state capital-- at the Conner trading post during the summer 1820 in preparation for their journey. Whether Conner gave serious consideration to trying yet another frontier is uncertain. As early as 1818 he petitioned to secure legal right to his land, but whether this was with an eye toward remaining or simply securing payment is unknown. Mekinges assumed he, like his partner Marshall, would go with his family, but became "very anxious and much worried" when William made no preparations to leave. When the wife of famed Indian Agent John Johnston confronted Conner, he denied any intention of staying behind. Conner may have also considered keeping his family in Indiana, as he filed a petition in 1820 saying he wished to have the land to raise his family. Conner claimed he begged his family to stay, but a future white in-law asserted he "sent them away."

In the end Conner chose to stay upon his land and watch his family go. Like his father before him he staked out a claim to his last frontier. Mekinges, distraught at leaving her home, planted sprigs of Live-forever for each of her six children around the homestead. She planted the rapidly growing shrub, she later recalled, because she wanted no one else to live in her home. William Conner divided assets with Marshall and provided his own family with horses and goods. Conner's family and the Delaware began their trek in the dwindling summer of 1820. Conner rode a day with his family before saying goodbye.

With his family's leave-taking William Conner began to retire his balancing act, his tripping dance with equilibrium was almost over. The years from 1820 to 1823 were ones of transition. Within three months of his family's departure he married Elizabeth Chapman, possibly the only young, eligible white women in the area, taking her into the home he had shared with Mekinges and his family. He and brother John [Conner], who had recently returned to the area, set about acquiring land and initiating business ventures. William Conner's tentative steps into the white world soon became determined strides. In 1823 Conner began the construction of his brick home, locating it on a terrace edge overlooking the White River less than one-half mile south of his log cabin. Little is known about the building process. Tradition says it was built by craftsmen from the "east." A deposit of bricks later uncovered east of the house supports the claim that the bricks were fired on site. The result was a Federal style house that became a focus for activity of all sorts in the rapidly expanding area.

Trowbridge-- who was forced to send to Ohio for a Delaware who could help answer his questions, so successful had been the removal efforts-- was not the only visitor to the home. It became a stopping point for many travelers, businessmen, and politicians. Indianapolis lawyer and civic leader Calvin Fletcher thought the homestead and surrounding lands beautiful and newspaper owner Nathaniel Bolton was enchanted by the view of "fifteen or twenty merry plowmen" spied from the second floor of the house. The Conner home was also the de facto center of the newly formed Hamilton County government when it hosted the County Commissioners, Circuit Court, and served as a "post office."

From his new home Conner entered fully into the teaming world advancing toward him. Like his father he became a "facilitator" of settlement. He--sometimes with partners-- acquired ever-increasing amounts of land, acreage which could be profitably sold to new settlers. He and Josiah Polk platted Noblesville in 1823, shrewdly donating land for the county seat, and later Alexandria and Strawtown. At one point he owned approximately four thousand acres in Hamilton County. In addition to farming and stock-raising he expanded his business interests by owning or investing in stores, mills, and a distillery. In many ways he may be seen as a prototype of the entrepreneur. His enterprises ranged from small country stores to a larger one in Indianapolis for which he assumed responsibility after the death of his brother John in 1826. He appears to have been a crafty businessman. Conner sometimes resorted to complex, convoluted maneuvers, such as transferring his interests to partners temporarily if they were threatened.

By the 1830s William Conner was well established in his own "new world." He had become a respected figure. He made occasional forays into politics, supporting Whig policies. He served three non-consecutive terms in the state legislature from 1829 to 1837. His motives were probably more those of a businessman seeking to advance his interests than those of a man wishing to be a public servant. He was a founding member of the Indiana Historical Society, but appears to have done little beyond signing the charter. It must be noted that Conner did not entirely abandon his old world. In addition to aiding Trowbridge, Conner still dealt with Indian affairs. He was an interpreter for treaties with the Miami in 1826 and the Potawatomi in 1832. Also in 1832 he served as a guide for a group of Indiana militia who went off to take part in the Black Hawk War. The conflict being all but over by the time the group reached Chicago, he led them peaceably back to Indiana. Anecdotal evidence indicates Conner also occasionally harkened back to his earlier days by dressing himself and his children as Indians and frolicking about in an attempt frighten visitors.

Seven of William and Elizabeth Conner's ten children were born in their brick home. [Their children are listed under Mekinges. In 1837, in his sixtieth year, Conner moved his family to Noblesville, his final step into settlement. He continued to oversee his business interests, but eased into his final role as a pioneer patriarch. Life slowed considerably for the ever active man. When he died in 1855 many of the trails he helped blazed had become roads, many of the forests he roamed had been cut away to reveal towns. The Conner house rising out of the prairie remained. It is not known precisely who resided in the house in the remaining years of Conner family ownership. It is likely it was occupied by some of the children or, possibly, tenant farmers. Ownership of the property was not without controversy. It was the subject of legal disputes, including an unsuccessful attempt in the 1860s by Conner's Delaware children to gain title to the land on which they were born.

The land passed out of Conner hands in 1871. It went through several owners until purchased by Indianapolis businessman Eugene Darrach in 1915. During that time the house underwent changes, the most notable being the addition of a kitchen ell. Although Darrach seems to have made some effort to maintain the home-- and allowed the placement of a historical marker on the grounds-- the house continued to deteriorate. In 1934 the 111-year old house fought time as it awaited its savior.

Timothy Crumrin is Historian/Archivist at Conner Prairie. He holds an M.A. degree in American History from Indiana State University. His works include The Voice of the Hammer: The Art and Mystery of Blacksmithing, Indiana Alma Maters: Student Life at Indiana Colleges, 1820-1860 [editor], and scholarly articles. The Conner Prairie Web Site contains many other articles of interest. http://www.connerprairie.org .

The Conner Estate is one of the crown jewels of Conner Prairie. William Conner was a fur trader, land speculator, entrepreneur, interpreter, and legislator. He came to Indiana in the winter of 1800-1801 with his brother John, married a Delaware woman named Mekinges, and established a trading post along the White River. Following the removal of the Delaware, he built his handsome brick residence for his second wife, Elizabeth Chapman Conner, in 1823. The Conner family lived there from 1823 to 1837, when they moved to Noblesville, Indiana, a town founded by Conner and a partner.

After passing out of Conner family hands and falling into disrepair, the house and grounds were purchased by industrialist and history-lover Eli Lilly in 1934, who repaired and restored the home. The Conner Estate underwent a further restoration in 1992 and appears much as it did in the 1820s. Optional 30-minute guided tours are scheduled every 20 minutes and may be reserved on the day of your museum visit. The estate also features a large barn, loom house, spring house, and a demonstration garden. Visitors may watch interpreters reproduce coverlets and blankets, and demonstrate the weaving, spinning, and dyeing of cloth. The Conner House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. For an article on the furnishing of this historic house, including photographs, see www.connerprairie.org/chfurn.html .

A document in the Bartlesville, Oklahoma,

Library provides these data:

Conner, Richard C. [birth and death dates to be added.

Irishman of Maryland. Married

Margaret Boyer (birth and death dates to be added], German captive of the

Shawnee

1. James Conner, 1771, in Detroit

2. William Conner, 1773 [?]-1855.

He married first in 1802

ME CUN CHIS/Elizabeth Anderson,

1789-1862/1867, daughter of Chief Wm. Anderson, a 1/2 Delaware [Her ancestry is a matter of debate. See

MEKINGEES/MEKINGES/MEKINGIS in the Biographies.

He married second Elizabeth Chapman, a white

woman.

* * *

FALL LEAF, Captain - From Richard C. Adam, Delaware Indians: A Brief History: I invite the reader's attention...to a letter from Captain Fall Leaf, in which he recites some of the important events of his military career. As a scout he was many years in the employ of the United States Government. As a mark of the distinguished regard and confidence of Government officials of that day entertained for him, in 1860 he accompanied the Prince of Wales, now Edward VII of England, whilst he was touring this country.

Delaware Reservation, September 15, 1863.

DEAR SIR: I was employed by Colonel Summer about four years ago to guide seven companies of soldiers under him in an expedition against the Cheyennes. I selected six companies of Delawares and did the work assigned me. We whipped the Cheyennes that time and were discharged by Colonel Summer and paid off. Colonel Summer, however, in addition to the money paid me, promised that the Government should give me 160 acres of land. I have never received this land and I would be glad to have you write to me how to get it.

Colonel Summer told me after we were discharged, that if at any time thereafter I should want anything, that I should call on you and you would grant it.

One year afterwards I was again called upon by Major Sedwick, and , with six Delawares I selected, I guided three companies of soldiers under the major against the Kiowas and we whopped them also. Major Sedwick also promised me land, and, like Colonel Summer, told me whenever I wanted anything to call upon the Government and they would grant it.

Again in the fall of 1861, at the request of Major-General Fremont, I raised a company of 54 Delawares and proceeded under the instruction of Maj. F. Johnson, our agent, and at the request of General Fremont, to Springfield Mo. We had no fight this time, but we did all that was required of us, and we went back to Sedalia with General Fremont and then he paid us off and discharged us. At this time also, General Fremont promised me 160 acres of land and told me also that that at any time I wanted anything of the Government to let them know and I should surely have it.

In the summer of 1862 I went out under Colonel Ritchie of Topeka, Kans. (and had a fight near Fort Gibson; we saw the enemy, the Choctaw Indians, the half-breed, we play ball with them, 50 we laid on the ground, 60 we took prisoners, even the Choctaw general; him I took myself alone; he was a big sesesh; 100 Union men he had killed. I brought him to the Cherokees; they killed him; they gave him no time to live), and Colonel Ritchie made the same promise that the other officers did. I was captain of a company of 86 Delawares, under Colonel Ritchie, for about four or five months, and have not yet ever received one cent for these services, nor have any of my men yet been paid for these same services, although we all served faithfully and furnished our own horses.

I write to you now to ask you to see that I get pay for all these services, according to promises made me, and that my men also get their pay. We have always served the Government of the United States faithfully whenever the Government keeps its promise to us.

I am, respectfully, CAPTAIN FALL LEAF. PAUL JORDAN.

I forget one thing more. We wish that you would ask the President to send our men back home. We do not wish to have them discharged away from home. We want them sent back home and then discharged. We are afraid of our homes, and we want the men at home to protect our women and children, and our own property. We wish that you would also let us have about 200 guns, with powder and lead, so that we may be ready in case any danger arises at any time.

You will please direct your answers to CAPT. FALL LEAF (Care Wm. McNeil Clough, Leavenworth City, Kans.)

Hon. W. P. DOLE, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Washington City, D. C.The following item from www.larryville.com (Lawrence, Kansas) has quite a bit of information about Captain Fall Leaf and the Delaware in the Lawrence area:

Delaware Street Rag

by Michael Caron mcaron@sunflower.com*First Song: XENGWIKÁON Verse XII: [A Story]

Before we left the Lawrence Airport that morning Mary [Zeigler] told me another thing about the Lenape presence in North Lawrence that I had never heard in all those years of Mumi retelling . In all those years of listening to Mumi retell what Mary had said about the Big House I had never realized that the last of the truly traditional Big House ceremonial sites was located somewhere just east of the airport. Fall Leaf's band had a special roll in the Gamwing, the Celestial Bear Ceremony, and other sacred gatherings through the annual cycle of the XENGWIKÁON. Thus the Big House was near Fall Leaf's settlement, just to the east of the great communal cornfield. Even after the majority of Lenape began to neglect the rituals Fall Leaf's followers seemed determined to preserve Lenapeness through traditional ritual and song. His people were among the last to leave their homes in Kansas. Mary Zeigler's ancestors were prominent in this band of the Lenape living across the river from Lawrence. Many Zieglers were buried in the Delaware Cemetery at the north end of the bridge to Eudora. Some of Fall Leaf's band, including Mary's great grandfather and other relations, were still present to see Governor Robinson's hirelings pull down what was left of the old Big House log by log to recycle as an out building for his farm.

A few of the traditionalist Lenape, men from Fall Leaf's band prominent among them, had tried to resurrect the old ceremonies after their move to Oklahoma. The famous mixed blood Algonquian anthropologist Frank Speck had even taken photos of "the last Big House" in Copan. But Speck's informant, one of the few remaining practitioners of traditional Lenape religion, made it clear that the last real Big House, the last place where all the ceremonies had occurred in their rich and full form, had been the one in North Lawrence. So much was lost by the time those few elders with any knowledge undertook the task of revitalizing the rituals and rebuilding the Big House near Copan.

According to Mary that last Big House in North Lawrence was an early and frequent victim of massive Jayhawker and Bushwhacker vandalism and thievery. But she also described how even before Kansas was opened to white settlement the Christian missionaries played a crucial part in the neglect that befell this sacred site. By the time the great Kansas River flood of 1840 put the Big House under water it was already in serious decline. Some Lenape, like Speck's informant, believed that the neglect of the Gamwing was the ultimate cause of what happened when the Jayhawkers came flooding in from the east just over a decade later. All the Indians of Kansas suffered incredibly under the growing weight of white squatters and speculators. Their livestock and crops were stolen, even their seed for the next year's planting was taken by the people who moved into the area. The nightriders terrorized the Indians in hopes of driving them from the best lands. The town speculators struck deals with individual Lenape for timber they had no authority to sell. Squatters cut and hauled away the best of the trees even before men like Senator Lane and Governor Robinson could arrange to have their own crews harvest the timber they had plotted to steal from the Lenape. The Indians were reduced to starvation and to a daily life of overwhelming terror. Ironically the U.S. Army, which had established a fort at Leavenworth in order to guarantee the protection of the eastern tribes, stood aside while the whites cleansed Kansas of its Indian population. Fort Leavenworth was built on the very site that the Lenape had originally selected for their Kansas home, the first of many fundamental violations of the treaties that brought 10,000 eastern Indians into this part of Kansas. Most of the officers at Leavenworth lined their pockets with profits made helping civilian associates steal Indian land and timber. Mary claimed that half the shareholders in the town company that became Leavenworth were officers from the fort, men charged with responsibility for insuring that those squatters stay off that most valuable of all Lenape land in Kansas.

By 1867 the Lenape, once arguably the most powerful and influential native nation in all of eastern North America, were put in such desperate straights that all they could hope for was that somehow they might find a way to survive as a distinct people. Old Fall Leaf wrote to Washington that his tribe was known as the Delaware, and that they had been a nation since long before there had existed any such nation as the United States. "For time to come, as far as human mind can conceive, we wish to be a nation." Survival as a distinct people was the best he could dream on his empty stomach as he watched the small children and elderly dying of hunger all around him. He knew that his people could not hold on to their Kansas homes any longer. Be done with it. Stop the torture and abuse. Let my people go. But federal government agents insisted on using this great opportunity to force the Lenape into accepting a relationship with the Cherokee tribe of Oklahoma that would wipe out their distinctiveness as a nation. To get land in Oklahoma, in what was then the much reduced "Indian Territory", the Lenape would have to agree to be absorbed into the Cherokee Nation. So the government inflicted starvation went on and on. The pressure from the surrounding sea of whites, slaveocrats and freesoilers alike, just continued to mount. In his broken English Fall Leaf begged for mercy from his white neighbors, and for the Delaware Indian agent to release the supplies promised in the treaties:

"We do honest want to have it done. Because since 4 years we have lost what little was left then. and crop fail, and every Article of the kind we need is very high in price. We wish our Great Father should be kind give such as is need Now. even no seed to plant. We should like to have it done right off. for God sake. and Remember the treatys, we hope Government should listen our suffering nation."

* All the verses except Verse XII can be read at the larryville web site.

Verse I: From Thule to Oz

Verse II: Ponsetunik ("This place is swarming with NATS")

Verse III: Haki's Fabulous Froggers

Verse IV: Lenape Historical Geography

Verse V: The Quodbas and Other Magic

Verse VI: Otava, the Great Sky Bear

Verse VII: Big House

Verse VIII: Diffusion by Shawnee Allies

Verse IX: The Zeigler Stay Behinds

Verse X: Mixed Blood

Verse XI: The North Lawrence Cornfield

Verse XII: Fall Leaf's Band

FALLEAF, George - From his obituary in Ruby Cranor, Some Old Delaware Obituaries, p. 28:

Falleaf was honorary chief of the Delawares. There has been no chief since Chief Journeycake died several years ago. Since then a committee has had charge of tribal affairs. This committee gave Falleaf the title of honorary chief in recognition of the high regard in which he was held and because he was one of the oldest living Delawares. He was long considered one of the most able men of his tribe and was called upon to represent his people in Washington on several occasions. He was held in high esteem throughout this section by both Indians and white people. Falleaf was a son of Captain Falleaf who commanded a company of Indians during the Civil War. He was one of the two male members of the Delaware migration from Kansas. His death Sunday at the Indian hospital in Claremore leaves Charley Elkhair the sole male survivor. There are several Delaware omen living who made the trip. Falleaf was a scout under General Miles. He and 20 other Delawares organized a band of Indian scouts at Coffeyville and went to the western plains to fight warring tribes for the government. The father of Falleaf was a captain in the U.S. Army. He is also buried at Cotton Creek Cemetery. Bartlesville Examiner, September 12, 1939.

FISH, Arch - A Shawnee Indian. He had children with Betsy Wilaquenaho on the Delaware Reserve in Present Kansas. Their children were Eliza Jane Fish and Sarah Ann Fish, whom see.

FISH, Eliza Jane - Revised 25 November 2001. Eliza Jane Fish is the daughter of Arch Fish and Betsy Wilaquenaho Fish-Marshall. We had earlier thought that she was the daughter of Betsy Wilaquenaho and William Marshall. Eliza Jane Fish is No. 961 on the Register of the Delaware Indians Residing in the Cherokee Nation, as a Tribe and Individuals Showing Their Lands, Improvements, Location and Valuations of Improvements in Possession of Them Prior to and on August 4, 1898. This document shows that she died prior to the date of the document. Her husband was shown as Charles Lavin, age 56, but his name is crossed out. Also crossed out is his (or their) land holding of 160 cultivated acres with 160 acres enclosed, valued at $500.00. Mary Ann Tiblow at 76 [born ca.1822] is listed as a sister as is Sarah A. McCommish at 57 [born ca.1841]. This ties all three of these sisters as daughters of Betsy Wilaquenaho (listed as Betsy Marshall, Register No. 962). John Marshall age 41 [born ca.1857] is listed as her nephew. Note a gives the names of the witnesses, Jno. McCracken, Henry Armstrong, H. M. Adams. Note b "Remarks" says "One mile southeast of Silver Lake." The note also says, "See Reg. 939, 963 for improvements." Note c says (crossed out) Nov. 4, 1898, Jan. 2, Apr. 118, 1899. Reg. No. 939 is for Henry Tiblow, deceased and Mary Ann Tiblow (wife) 76. Note b (remarks) says 1/2 mile S. of Willow Springs School House. (Faye Louise Smith Arellano, Delaware Trails: Some Tribal Records 1842-1907, pp. 452-453)

Sarah

Ann nee Fish Rankins McCamish

(Provided

by Bonnie Wear)

We had thought earlier that

Sarah Ann (Fish) Rankins McCamish was the daughter of

Betsy

Wilaquenaho and William Marshall. Sara Ann was born

ca.1836-1839 on the Delaware Reserve (present Wyandotte County, Kansas,

the daughter of Betsy Wilaquenaho and Arch Fish. Her mother, Betsy

Wilaquenaho (possibly Ketchum) was first married to William Marshall and had

several children with him. He died in Greene County, Missouri in 1834. Betsy

Wilaquenaho had gone with the tribe to the Delaware Reserve, but we do not

know whether or not William Marshall ever went to Kansas. In any event, Betsy

had at least two children with Arch Fish after William's death, the other child

being Eliza Jane Fish. Arch Fish was

a Shawnee Indian. We know little about him, but are trying to determine his

personal and family data. Sarah Ann married 1. Samuel Rankin and 2. James McCamish/McCommish.

Saran Ann was on the list of the Delaware Who Elected to Remain in Kansas and Become

U.S. Citizens in 1867 under 1863 Allotment No. 72, but at some point after 1866

she went to Indian Territory (present Oklahoma). Her minor children from the same

listing under her name were the following with their 1862 Allotment Numbers:

No.

73 Alice Rankin, age 9

No. 1048 Sally Rankin, age 5

Verity P. Hamilton,

age 2.

From family data we have the following:

Roll Nos. 963/687 Sarah A.

Marshall [Fish] 1832 - married 1. Rankin 2. McCamish. [Children:]

---/685 Alice

J. Rankin born 1856

---/689 Sally/Sarah E. 1862

Verily Prudence died early.

Richard/Robert MacCamish born 1877.

From the Register of Delaware Residing in the

Cherokee Nation 4 August 1898, Sarah A. McCommish is listed as living at age 57

[born ca.1841] under No. 962 Betsy Marshall

"dead." (Faye Louise Smith Arellano, Delaware Trails: Some Tribal

Records 1842-1907, p. 452) She is also listed in the next entry under No. 963 "living" Sarah Ann Rankins alias

Sara McCommish at age 57, with 63 cultivated acres of land, 130

acres not enclosed, value $3,000. Witness were William Clark and Wm. Adams, and

Note b (Remarks) At Willow Springs Note c Jan. 2, 1899. Her children:

J. Lynch 24

Lizzie Lumbard 32

Richard McCommish 21.

Sarah Ann died 4 August 1898, probably in Oklahoma. From the Cherokee Nation Delaware Roll dated 31 1904 the following data are given: __________________ District, Ketchum, I. T., Sarah A. McCamish age 63, Tribal Enrollment as a Delaware No. 1707 in 1880, tribal enrollment of her father, Arch Fish, _____, listed as a Shaw.[nee] Indian, and her mother Betsy Fish. Other data on the document says No. 1 on Delaware Register No. 963 as Sarah Ann Rankins. No. 1 on 1896 roll page 623 No. 56 Del. Dist. On Delaware card No. 47 (old series) 1 October 1900. On this card March 31st, 1904. A search of the NARA internet data base reveals the following: Control Number NRFF-75-53A-DELAWARE (O[ld]S[eries]47, Record Group 75, Series 53A, Item DELAWARE (OS47), Title-Enrollment for Delaware Census Card )S47. Parents Arch Fish and Betsy Fish, [their child] Sarah A. McCamish, Type Old Series, age 63, full blood, Roll Number NR [not registered], City of Residence Venita. Variant Controls NRFF-75-53A-5486, NRFF-75-53A-6488, NRFF-75-53A-12514. See also: Series description: Dawes Rolls.

The Descendants of

Sarah Ann Fish from a Family Descendancy

Chart:

1. Sarah Ann Fish born about 1832-1836, spouse

Samuel Rankin (See photograph

above.)

2. Alice Jane Rankin born 16 July 1855 Kansas Delaware Reserve, died

1908-Indian Territory (OK)

Spouse: Charles William Albertus Lynch (born Feb. 1839 WV, married 1876,

died 18 August 1899 Ketchum, Oklahoma.

(See photograph below.)

3. Luther L. Lynch

3. Minnie B. Lynch

Children with Spouse: Elam Gregory

3. Ada J. Lynch

3. Mary Elizabeth Lynch born 9 Dec. 1887 Indian Terr. (Craig

Co., OK), died 6 Dec. 1980 Arcadia, CA

Spouse: John Francis Woolery born 9 Dec. 1877 MO, mar. 2 Sep.

1902, died 1956 Arcadia, CA

4. Mark Odel Woolery born 1 March 1905,

died 6 Dec. 1980 Loma Linda, CA

4. Aldena Cora Woolery born 13 March 1906

Indian Territory, died 29 July 1990 Arcadia, CA

Spouse: Thomas Rhoten Wear born 1 March 1899

Paris, AR, mar. 1 May 1928, d. 5 Nov. 1957

Glendale, CA

5.

Lawrence Gene Wear living

5.

Thomas Reginald Wear living

5.

Douglas Jonathan Wear

living

4. Wayne Francis Woolery

born 8 Nov. 1914

Ketchum, OK, died 17 July 1979 California

4. Minnie Wicona Woolery

living

3. Benjamin H. Lynch

3. Sarah F. Lynch

3. Charles William Albertus Lynch, Jr.

2. Sally Rankin born Jan. 1862

2. Lizzie Rankin born 1866, spouse Hamilton

2. Verity Prudence Hamilton born about 1865, spouse

William H. H. James

McCamish

2. J. Lynch McCamish born about 1873

2. Richard McCamish born 1877

In a statement made by

James McCamish in an interview in 1907 where he was trying to get listed on the Cherokee

Rolls in 1907, he said that Sarah Ann died the 25th of the previous month, that

is, 25 December 1906. James McCamish was 60 [born ca1847] at the time of the

interview.

(Provided by Bonnie Wear bonniewear@usa.net

)

Family of Alice Jane nee Rankin Lynch (Daughter of Sarah

Fish McCamish Rankin) (Provided by Bonnie Wear)

Left to right: Back

row: Luther Lynch, Minnie Bell Lynch . Second row: Alice's spouse

Charles W. A. Lynch, Alice Jane Rankin Lynch, Ada Jane Lynch.

Third row, Mary