From the

Encyclopedia of North American Indians we learn that

he was one of a set of triplets born at Old Piqua, on the Mad

Rive4 in western Ohio.

His mother was Methoataske (Turtle

Laying Its Eggs), a Creek woman. His father,

Puckeshinewa, a Shawnee war chief, was killed at the

Battle of Point Pleasant prior to the triplets' birth. The

triplets were the youngest siblings in a large family (they

had at least six older brothers and sisters), and one of the

triplets died in infancy. The other triplet, Kumskaukau,

lived at least until 1807.

In 1779 Methoataske left Ohio. The two

remaining triplets and Tecumseh, a brother born in

1768, were left in the care of Tecumapease, an older,

married sister. Their upbringing also was supervised by

Chiksika, a brother in his late teens. Both Tecumapease

and Chiksika favored Tecumseh, an athletic youth who excelled

at the contests and games popular among Shawnee boys. In

contrast, the boy who would become the Prophet was an awkward,

corpulent youth who accidentally gouged out his own right eye

while fumbling with an arrow. Because he often boasted and

complained, he was called Lalawethika (the Noisemaker),

a name he disliked. He married in his teens, but was unskilled

as a hunter and became an alcoholic. He did not participate in

the Indian victories over Josiah Harmar (1790) or

Arthur St. Clair (1791), but he did join a war party of

Shawnees led by Tecumseh who fought at the Battle of Fallen

Timbers. Following the Treaty of Greenville (1795) he lived

with a band of Shawnees led by Tecumseh who resided at several

locations in western Ohio and eastern Indiana. In 1798 they

moved to the White River near Anderson, Indiana, where

Lalawethika, still an alcoholic, unsuccessfully attempted to

assume a role as a healer and shaman.

In the decade following the Treaty of

Greenville socioeconomic conditions among the Shawnees and

neighboring tribes deteriorated. Game and fur-bearing animals

declined, while frontiersmen encroached upon Indian land,

poaching the few remaining animals and establishing new

settlements. White juries protected Americans accused of

crimes against tribes people while systematically convicting

Indians. Meanwhile, many Indian people contracted new diseases

for which they had no immunity. Under considerable stress,

tribal communities were plagued with apathy and dysfunction,

and alcoholism increased. Considerably alarmed, many Shawnees

believed that their troubles were caused by witches spreading

chaos in the Shawnee world.

During April 1805, in the midst of this

crisis, Lalawethika underwent a religious experience in which

he appeared to fall into a trance so deep that his family at

first believed him to be dead. After a few hours he recovered

and informed his neighbors that he had died, had been taken to

a location overlooking heaven and hell, and had been shown how

the Shawnees could improve their situation. He stated that

although Indians had been fashioned by the Creator, Americans

were the children of the the Great Serpent, the source of evil

in the world. Aided by witches (Indians who accepted American

cultural values), the Americans had spread chaos and disorder.

In consequence, he championed a new religious revitalization,

urging the Shawnees and other Indians to minimize their

contact with the Americans. He admonished tribespeople to

relinquish American food and clothing, most manufactured

goods, and alcohol. Firearms could be used for defense, but

game should be hunted with bows and arrows. If Indians

followed such doctrines, their dead relatives would return to

life and game would reappear in the forests; if they refused,

they would be condemned to a fiery hell reminiscent of

Christian doctrines. He also announced that thenceforward he

should be known as Tenskwatawa (the Open Door), a name

befitting his new role as a prophet.

Tenskwatawa's teachings found many adherents

among the Shawnees and neighboring tribes, particularly after he

successfully predicted an eclipse of the sun in June 1806. By

1807 so many Indians had traveled to his village near

Greenville, in western Ohio, that they exhausted food supplies

in the region. White officials became alarmed at this influx,

and in 1808 the Prophet led his followers to Prophetstown, a new

village near the juncture of the Tippecanoe and Wabash Rivers,

near modern Lafayette, Indiana.

In 1809, after the Treaty of Fort Wayne,

Tecumseh attempted to transform the religious movement into a

centralized political alliance designed to retain the remaining

Indian lands in the West. From Prophetstown Tecumseh traveled

throughout the Midwest. In November 1811, while Tecumseh was

recruiting allies in the South, William Henry Harrison,

the governor of Indiana Territory, led an expedition against

Prophetstown. Forced to protect his village, Tenskwatawa

promised his followers that they would be immune from American

firearms and instructed them to attack Harrison's camp. In the

resulting conflict, the Battle of the Tippecanoe, the Indian

attack was repulsed. Although both sides suffered losses, the

Prophet's influence was broken. When Tecumseh returned from the

South in January 1812 he assumed sole command of the Indian

alliance

Never a warrior, the Prophet took little

part in the War of 1812. In December 1812 he fled to Canada,

then accompanied Tecumseh back to northern Indiana. In the

following spring they led a large party of western warriors to

the Detroit region. The Prophet accompanied the British and

Indian forces that unsuccessfully besieged Fort Meigs during

May 1813, but he took no part in the fighting. On October 5,

1813, he was present at the Battle of the Thames, but he fled

with the British when the battle started. Tecumseh was killed

in the battle.

Following the War of 1812, the Prophet

remained in Canada for ten years, unsuccessfully attempting to

regain a position of leadership. In 1825, at the invitation of

Lewis Cass, the governor of Michigan Territory, he returned to

the United States and used his limited influence to promote

Indian removal. One year later he accompanied a party of

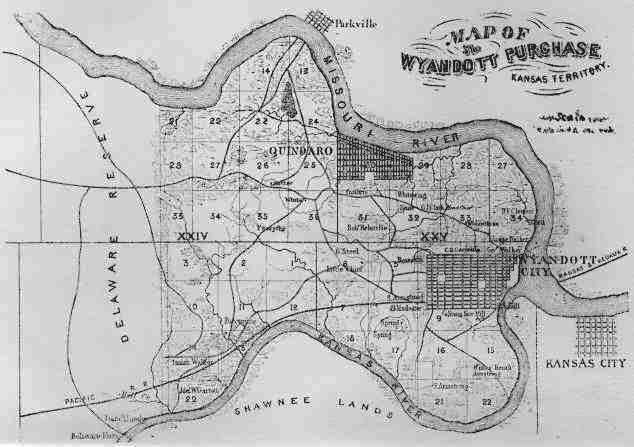

Shawnees from Ohio who were traveling via St. Louis to Kansas.

The Prophet settled at the site of modern-day Kansas City,

Kansas, where he posed for the artist George Catlin in the

autumn of 1832. He died there four years later, in November

1836.

The Encyclopedia of North American

Indians was published by the

Houghton-Mifflin Company of Boston and New

York, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New

York, 10003. Encyclopedia of North American

Indians / Frederick E. Hoxie, editor. p. cm.

Includes index. 1. Indians of North

America—Encyclopedias. I. Hoxie, Frederick

E. E76.2.E53 1996 970.004'97'003—dc20

96-21411 CIP Book design by Anne Palms

Chalmers (Potawatomi ancestry). ISBN

0-395-66921-9. We highly recommend this work

to our readers.

|

|

|

|

|

|