The "Big House" was the main religious

building of the Delaware Indians.

It was used for an annual religious ceremony to thank the

Great Manitou and the

lesser Manitou

for the good fortune of the last year and to pray for protection from

future calamity and destructive natural forces (manitou was their word for

spirit or deity).1

The purpose of this paper is to examine the complex ways in which the Delaware

Big House can be read semiotically as a cultural text that demarcates the

social, religious and political reflexivity of the culture.2

The array of signs and symbols that are imbedded within the architecture will be

described through an analysis of its conception, construction, and use. Within

these three larger processes, I will look at how the Delawares formed, informed,

and transformed themselves through their use of symbols.

CONCEPTION

The conception, or plan, of the Delaware Indian Big House was based on an origin

myth in which the building's purpose was explained, its decorative images

prescribed, and its appropriate uses dictated.3

Through the myth of the Big House, the Delawares addressed their fears of

nature's destructive forces. The myth explained that "long ago the very

foundation of life itself, the earth, was split open by a devastating quake."

From this opening in the earth, "The forces of evil and chaos erupted from the

underworld in the form of dust, smoke, and a black liquid."

The humans then met in council and concluded that the disruptions had

occurred because they had neglected their proper relationship with the

Great Manitou. They prayed for power and guidance. The manitou spoke to

them in dreams, telling them to build a house that would re-create the

cosmos and how to conduct a ceremony that would evoke the power to sustain

it.

This

segment of the myth subtlety informed the Delawares about how they formed. This

can be seen in the first line of this section where it says "The humans then met

in council," or came together in order to jointly explore and define the actions

of the natural (and supernatural) world and to address the reordering, or in

reality, coming to terms with the cosmos. In this indirect way, those with

religious and/or political power set the stage upon which they would dictate,

through symbolic representations, the rules by which the members of the society

would be expected to abide by.

By "telling them to build a house that would re-create the cosmos," the myth

transformed the house into a symbol. For the Delaware the universe consisted of

twelve houses stacked one upon the other. The Great Manitou resided in the

twelfth and highest house. When entering the Big House, the people envisioned

themselves as passing through these twelve stacked houses. In the form of the

Big House, the concept of "house" acquired meaning beyond that of its individual

existence in and of itself.4

In the myth, the buildings

interior decorative motifs were set out in rough form. The myth goes on to

explain that the Big House Ceremony, "would establish their moral relationship

with the Manitou." Inside the building, the myth told thein to carve faces of

their gods on wooden posts. In their ceremonial dance, they would stop at each

mask and speech to it as if it were alive. The building , then, facilitated a "

face to face" encounter with their gods. These recitations were believed to

"renew and revivify the individual's relationship with his or her personal

manitou."

Symbolically, by building the Big House, the Delawares could right what they had

made wrong, to balance what they had made unbalanced, and thus protect

themselves from total destruction. The myth informed the people as to what kinds

of associations belonged with the Big House. From this, it was determined what

symbolic forms these should take, what symbolic action should occur in

conjunction with these objects, and how these would interact with the individual

and, ultimately, with the group.

According to this myth, the Delaware also had to follow certain guidelines using

the Big House to maintain this fragile sense of order. These primarily had to do

with cleanliness and purity.

The old time was one of impurity, symbolized by dirt and smoke. To make

the transition into sacred time everyone and everything had to be purified

including attendants, reciters of dreams, and the Big House itself.

Purifying fires burned on either side of the center post. Persons or

objects in a state of impurity, such as menstruating women were always

excluded from the Big House.

This

piece further informed the actions of the Delaware, as well as substantiating

that the Big House and all the dictates that went along with it did, and will,

transform the world and the Delawares from a lesser, more dangerous position or

situation to one of greater stability. The myth made this transformation appear

as if it were reached and maintained by consensus of the whole of the Delaware

people, guided by a supernatural being, instead of by only those Delaware in

positions of religious and/or political authority.

With

the rough form and proper use of the Big House "supernaturally preordained," the

Delaware Indians were then given the task of transforming the mythical

conception into a concrete, visible, and functional form. The myth told them to

recreate the cosmos in the form of a

house. They had two types of house forms to choose from, the rectangular floor

plan of their permanent dwellings, the

longhouse or the circular plan of their temporary winter structures, the wigwam

.

The

longhouse was relatively narrow in width and could range in length from twenty

to four hundred feet, depending on the number of families living inside. Its

interior was divided off into sections about every twenty feet interval with

each section representing one family's living space. As additional room was

needed for new families, new sections could easily be added on to the end of the

longhouse. The long walls bore two rows of shelving, about five to six feet

wide. The top shelf was for food storage while the lower was for sleeping. Each

family area had its own fire pit and smoke hole.

The

longhouse form was selected for the Big House over the wigwam even though the

wigwam was much easier to build. From the Delaware's reverence for the circle in

their symbolism, and its ease of construction, it would seem more logical for

them to have chosen the wigwam. So it seems that the selection of the longhouse

form for the Big House was based on some other criteria than its ease of

construction or the natural symbolism in its form.

There

are four aspects of the longhouse that probably led to it being chosen. The

first reason was the capability of the longhouse for horizontal expansion. In

Delaware religious belief, the universe was conceived of as twelve houses

stacked one upon on another with the Great Manitou residing in the upper most

house. In a sense, the longhouse, was composed of separate family

units that were "stacked" end to end. The

longhouse depicted horizontally the vertical conception of the mythic cosmos.

Therefore, the longhouse was better

equipped for communal living. As a result, the longhouse form was more

easily transformed into a symbol of unity and communal relations with the

gods and the entire cosmos.

Unlike, the wigwam, the longhouse embodied permanence and stability. The wigwam,

being a temporary structure, would not seem suitable to represent a cosmos or

universe that is permanent and timeless.

The final aspect of the longhouse that led to its transformation into the Big

House was the importance the Delawares placed on an orientation with the four

cardinal points.5

Being rectangular, the longhouse could be easily oriented. Directional markers

served important functions within the Big House ceremony.

As a

result of its inherent, latent symbolism, the longhouse form was commandeered

and transformed into the Big House, creating a new form packed with systems of

symbolism, based on their powerful referential to other symbolism systems.

The

siting and orientation of the Big House symbolized religious beliefs and were of

major importance in the "framing"

of the Big House structure and

ceremonial actions within the larger community.6

Adopted from the established longhouse form, the Big House had to undergo a

transformative process from secular to sacred. The Big House had to be

physically and cognitively differentiated from its parent domestic form. This

was accomplished, in part, by stripping the interior of all bedding and shelving

structures, familial section divisions and secular decorations and objects. This

action removed all the symbolic structures that had framed the longhouse form

into a place of domesticity- a home.

New

symbols were conceived to correspond with the origin myth and the social,

religious, and political aims of those with authority. The more a ruler could

control their people's thoughts, beliefs, and actions, the more power they could

have. Power is invested onto the ruler by society's willingness to be

controlled, manipulated, or governed. The specific form this successful

manipulation took was of little import. It was only important to the elite that

manipulation had been allowed.

The

Big House was a long, narrow, rectangular building, placed on an east-west axis.

It had only two doors, placed at each of its narrow ends. The doors accommodated

the symbolic entering and exiting of the celestial bodies, the sun and moon. As

the sun and moon enter the sky world in the east and exit it in the west, so

shall the people enter the re-created cosmos of the Big House.

The combination of physical architecture, mythical movement, and human action

assist in the framing of the Big House as a sacred site. This east-west line

also reflected the Delaware's concept of the "Good White Path," the path man

travels through his/her journey from birth to death.7

CONSTRUCTION

At

certain times of the year, as prescribed by the origin myth, the elders taught

the young how to gather materials, use the tools, and employ the proper methods

for constructing the Big House. The act of teaching, although seemingly innocent

and devoid of ulterior motives, could also have been motivated by power

politics. Limiting what was taught, when, and to whom, served to empowered the

possessor of this special knowledge. If a person gave away all they knew, all at

once, they would no longer be of much value to their students or the larger

society. So by doling out knowledge in spoonfuls, a person confirmed and

strengthen their membership in society.

Rebuilding took place every time a clan relocated. Therefore, every time they

moved they symbolically recreated the universe at the new location. The building

and periodic rebuilding of the Big House represented the renewal of the cosmos.8 Repetition is an

extremely strong tool for indoctrination. By

repeating a symbolic, ritual action, the ideology behind the symbol becomes

absorbed into the unconscious thought patterns of the participants. By this

method, what were once consciously abstract ideas are transformed into concrete

"facts."

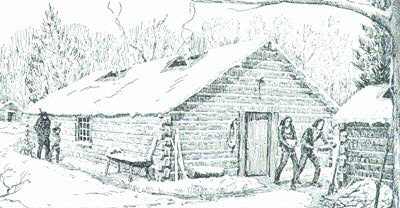

In its earliest known form, the Big House had an arched roof supported by

saplings which were fixed in the ground, bent over and the other end planted in

the ground (fig.3). Each arched sapling, conveniently, created the Good White

Path in miniature. In the second half of the 19th century, the Big House took on

a gabled roof. The poles which formed the Big House's skeleton were tied with

strips of inner bark or root fibers in a cross pattern that represented the

"cosmic cross" and referred to the four cardinal points. These construction

elements, bent or tied wood, served the interests of several symbolic systems

simultaneously: the "Good White Path, the cosmic cross, and the four cardinal

points. Together, this set of symbols, corresponded with the ideas of "joining

or binding together," one of the major purposes of the Big House ceremony.9

The

ribs and poles were then covered with wide strips of bark, usually from elm

trees, that had been carefully removed in one piece. The removal of the bark

required concentration and great care in action. Here, even in a small way,

manipulation is further witnessed. By dictating that bark be used for covering

the Big House skeleton, the authorities created a set of

prescribed, focused symbolic actions that had to be repeated over and over again

by the builders. The bark pieces were held into place by external poles pressing

the bark against the interior poles. The bark is, was a sense, sandwiched

between two sets of poles. In its early barrel-roofed form, the Big House and

its bark covering may have symbolized the "cosmic tree."10

By about the year eighteen hundred, the Delaware began to extensively use log

construction and the best descriptions of the Big House we have from the early

twentieth century show a sophisticated use of log joinery, in which the cosmic

tree may have been symbolized through the elements rather than the overall form.11

As

stated in its origin myth, the Big House, and all that entered into it, had to

be pure. For this reason, no metal objects of any kind were allowed in the

construction or use of the Big House. No metal nails could be used in the

joining of structural members, but if nails were needed, bone pieces were used

in their place.

This

also could have been an attempt to put forth or further a wish to maintain the

use of only materials found natural in nature or to keep a form that could be

constructed independent of manufactured goods. In this way, the Delawares could

remain independent of whites and could take apart, move, and reconstruct the Big

House with relative ease. Worn out members could be

replaced at any time by the surrounding trees

and other natural resources.

It can

also be speculated that this was another way to control the crowd. By requiring

that all participants remain clean and pure during the course of the ceremony,

coupled with the other symbolism in operation, a general attitude of reverence

could be obtained. This would be desirous to maintain conformity, consensus,

control, and peace. If participants were unbathed, and participating in secular

and/or lewd activities during the period set apart for the ceremony, the power

of the ceremony would be lessened. The Big House, its decorative symbols and the

ceremony would have difficulty in retaining meaning and, ultimately, power over

the members of the community.

The

walls, like the cross ties, represented the four cardinal points. The walls

created a closed, bounded space for the enactment of re-creating and sustaining

the cosmos. The Delaware indicated that, by the very nature of the world, all

humans were bound together by the four cardinal points. Dictating that the walls

of the Big House represent these four cardinal points, fell in line with the

notion of the Big House as a model of the recreated universe.

One of

the main purposes for the Big House and its ceremony, in addition to its

intensive religious role, was to unite or bind the various clans and their

members together in a close spiritual, social, and political association. This

was accomplished not only by making use of the symbolism of the four

cardinal points, but also by creating a

structure that forced participants to face one another in a close narrow space

that was shut off from any outside distraction.

The

structure served to create harmony with the natural as well as the supernatural

world. The floor was made of well tamped dirt and represented the lesser deity,

or Manitou, of Mother Earth. The purpose of keeping the floor well tamped was to

prohibit the raising of dust. As mentioned in the origin myth of the Big House,

dirt and dust symbolized the impurity of the old evil time.

The

ceiling represented the sky, the domain of the "Elder Brothers" the sun and

moon. Only two holes pierced the ceiling, one above each of the two sacred

fires. Some scholars believe that the two fires and the two holes in the ceiling

indicated worship of the sun and moon. In his Semiotics, Preziosi

demonstrates how common many of the symbolic associations mentioned above are.

The ceiling of a structure is

simultaneously meaningful systemically, as a component in the formal

definition of a space cell, and may also be significant in a given corpus

sematectonically, as in the case where the ceiling of a house or temple is

intended to symbolize the heavens (in contrast to the walls, which may

symbolize four cardinal directions of the horizon, and in contrast to the

floor - paved or not paved which may symbolize the earth, the underworld,

and so forth)12

In order to physically and cognitively

separate the Big House from

other house forms, no internal decorations were allowed inside, except for

twelve faces carved on eleven poles, three on each side of the long walls,

two on each door way, and two faces carved on the center pole . These were

the faces of the lesser manitou as prescribed by the origin myth and were

ritually painted during the Big House Ceremony. These faces represented

the Seven Thunders, the Four Cardinal points and Mother Earth (The Seven

Thunders had features of both man and bird and provided rain for the crops

and protected man from water monsters. They were also in control of

lightning).

Faces also represented an individual's personal manitou or spiritual guardian.

As part of tribal puberty rights, initiates go on a guest in which they

fasted and isolated themselves until they had a vision. In this vision, a

spirit, feeling pity for them in their hunger and isolation, would offer to

become their guardian. From that day forward, that spirit would be ever

present with the person. Thanks for guidance and protection was given to these

personal manitou at least once a year, usually at the Big House Ceremony.

The

center pole could have represented either the Great Manitou himself or else

the cosmic tree which reached up through the multilayered universe to the

Great Manitou. The cosmic tree was regarded by the Delaware much like many

other culture's "tree of life." This central pole was also referred to as the

"navel of the world." This "navel" belief was also common among the ancient

Greeks 13

USE

Conceived of mythic origin, and constructed according to symbolic rules, The Big

House was now ready to negotiate human action in order to illicit reflexive,

symbolic associations. Delaware society consisted of three clans or phratries:

Wolf, Tortoise, and Turkey. The Big House Ceremony was hosted by one clan or phratry who invited other neighboring phratries to participate. This was a way

of uniting the people for socialization. The Big House physically became the

center of all activity within the encampment. Visiting phratries set up camp

around the Big House and arranged themselves first by gender then by phratry.

This was reflexive of the real social structure in which men and women

participated in distinctly different work, were often physically separated due

to this differentiated work, and were symbolically endowed with different types

of spirituality. Women camped to the north and men to the south.14

This separation also symbolized the dictated celibacy of the participants.15

According to the myth, the past evil world was impure. In contrast, the

re-created cosmos, as represented by the Big House, was to be absent of all

impurities. Therefore anything that would taint a person was to be controlled.

Any uncontrollable impurities, such as menstruation, eliminated a person's

eligibility for participating in the ceremony. For this reason, sexual

abstinence was required and menstruating women were kept separate. The

segregation of men and women within the encampment symbolically guarded against

corruption.

Within the Big House, fires were prepared and tended by the men. No women were

allowed inside until the fires were lit. Outside, women prepared the ceremonial

foods: corn mush, dried meats, and berries. They placed them in wooden bowls

accompanied by shell spoons.16

In preparation for the ceremony, women swept the Big House twelve times. The

number twelve played a major role in Delaware Indian belief. For them, the

universe consisted of twelve houses stacked one upon the other with the Great

Manitou residing in the twelfth and highest house. When entering the Big House,

the people envisioned themselves as passing through these twelve stacked houses.

Within the Big House structure, there were twelve faces carved on the eleven

poles. During the ceremony, dancers paused at each face and recited verses to

them. Between each dance, the Good White Path was swept twelve times with a

turkey feather. Prayers to the Manitou were always said twelve times. The Big

House Ceremony usually lasted twelve days.

To

purify the Big House and its inhabitants cedar leaves were

burned. Between dances, tobacco was smoked to

maintain purity and to please the manitou. The sensual burning of these organic

materials and the fragrant scents they created, symbolized the spiritual

purification of the participants and the building.

The

physical separation of gender and phratries in the encampment surrounding the

Big House was further maintained inside. Each phratry sat on the floor in a

special reserved area, within which women and men sat separately. Hierarchical

separation was also seen in that the hosting phratry's sachem (chief), the

Bringer-In, the caretakers, and drums (this is the term for both the instrument

and those who play them) occupied separate places of distinction. In a single,

largely undecorated room, without clear architectural divisions, the Delawares

framed themselves within their phratries and, within their phratries, within the

sexes. By this framing, they informed all others of their social affiliations.

The

animals that represented the phratries (Wolf, Turkey and Tortoise), were not

totemic in nature, rather they were seen as emblems or mascots. The Delawares

did not believe them to be their ancestors. They were chosen for specific

characteristics the Delawares revered. When different phratries came together

for the Big House Ceremony, they retained their separate identities by sitting

in different areas and displaying their phratry emblems.

Delaware society was matriarchal. The eldest mother was called chief maker,

because, although she herself, nor any woman, would ever rule, she appointed

chiefs and had the power to remove them.

A male could not marry a female of his same

phratry.

Although each phratry retained their individual identities at the Big House

Ceremony, one of the ceremony's main functions was to unite the Delaware people.

They came together in spiritual oneness, for the purpose of thanking and

appeasing the manitou. Within the enclosed, bounded, unbroken space of the Big

House, they formed a single narrative of praise, and raised one voice in prayer

to deter future destructive forces.

The

ceremony commenced after the host gave a thanksgiving address. He then started

the first song and dance. The snapping turtle shell rattle stuffed with corn was

an important symbolic object within the Big House and the corresponding

ceremony. In later times, these rattles were hung from the rafters over the Good

White Path. These rattles were used by the leader of the dance as he recited his

puberty dream quest or vision.

Following the Good White Path, the dancers preceded counterclockwise to

replicate the movement of the sun from east to west. This left orientation was

also seen in everyday ritualized action. The left hand was holy while the right

was unholy. This movement to the left was also believed to represent the Indian

belief in life after death.

As the

ceremony proceeded, the lead dancer stopped at each of the carved posts and

recited their vision while mimicking the actions of their personal

guardian-spirit or Manitou. This is an interesting element of the ceremony and

Delaware belief, for the dancer came face to face with their gods and gave

testimony to spiritual transformation.

The dance and song were individual creations. No one there, but the gods, knew

whether what the dancers said in his/her song actually occurred. The songs were

invented by the dancer. There may have been a set range of styles that were

considered appropriate for this recitation, but the final construction was

solely up to the individual.

As the

dancers made their way around the "Path", all in the Big House remained

standing, and many joined the dancer. While the dancer exposed the intimate

details of his/her puberty rites, he/she was visibly and symbolically supported

by the standing audience, the dancers who had joined his/her side in the dance,

and the receptive eyes of the manitou he/she faced at each verse's recitation.

Segregation of gender was maintained in one of two ways. Either the women danced

in a cluster as they made their way around or they danced in a separate circle

from the men.

In between dances, the Good White Path was swept, by both men and women, twelve

times with turkey feathers. During these intermissions, tobacco was smoked to

please the manitou, the fires were tended by male caretakers and cedar leaves

were burned. Also at this time, the bowls of corn mush, dried meat and berries

were passed counterclockwise about the Big House. Each person took but one

spoonful of the food, so that all could, and would, share the ritual ceremonial

feast.17

During

the course of the ceremony, the rattle was passed around and any male who wished

to recite his vision and dance could take up the rattle. The dances continued

way into the night until no one else wished to take up the rattle. The

participants then filed out the west door, raised their arms towards the heavens

and prayed twelve times in unison to the Great Manitou. After this prayer, a

great feast was held back inside the Big House.

On the final night of the ceremony, women could dance and recite their visions.

This segment began when the women entered the house from the east carrying

wooden bowls of grease paint. They painted the men's cheeks red and black. The

men then rose and painted the carved faces on the poles half red and half black.18 This part of the

ceremony was a later addition and represented the "False Being." It was said

that in a dream, a certain man of visions saw a powerful manitou whose face was

half red and half black and whose mouth was bizarrely fashioned. This false

being represented a powerful evil force. The man traveled to the east and saw

the creature, returned home, and cut a mask from a tree in the image of the

spirit he had seen. It was felt that something terrible would occur if they did

not let the "False Being" into the Big House and if they did not pay him

respect. This "False Being" was believed to represent the white settlers. The

red half of the face represented the Indians while the black represented the

evil, impure white man. Many believed that letting the "False Being" into the

Big House led to the decline and decay of Indian spirituality and culture.

During

the ceremony, one of the hosting participants acted out the part of the False

Being. He was the only person in the Big House who wore a costume that masked

his identity. His costume consisted of a floor length fur coat, bear skin

stockings, a great wooden face that was painted half red and half black and

carved with exaggerated mouth. He carried a tortoise rattle and at no time let

any part of his real body be seen. Ironically enough, the role of the "False

Being" was to rid the ceremony of those who were impure.

At the

end of the ceremony, the chief gave an arms length of strung wampum (beads that

functioned as money and were considered to be the heart of the Delaware) to

those who assisted in the ceremony. A bowl of loose wampum was passed around and

each participant took two wampum beads. When they exited the Big House for the

final time, they placed the two wampum beads in their mouth as they chanted

their final prayer. This was believed to represent the Delaware putting their

hearts in their mouth and praying from their hearts. The distribution of wampum

also represented a distribution of wealth. It also indicated that there was a

need for such a distribution. There must have been varying levels of wealth and

power within the tribe.

The

final acts of the Big House Ceremony entailed closing or sealing the cosmos as

represented in the Big House. The fires were extinguished, first the eastern

fire and then the western fire. The ashes from the fires were thrown out the

west door.

The

Big House Ceremony was usually performed once a year, unless calamity occurred

or seemed eminent, and then it would be performed as often as needed. In later

years, the role of the Big House was expanded to include other religious

ceremonies such as male puberty endurance tests. These consisted of bringing

another symbolically highly packed structure, the sweat lodge, into the Big

House. On these occasions, a symbolic structure was used to house another

symbolic structure. But as time passed, the sacred use of the Big House was

expanded further to include political activities. When it became a common

meeting place for the tribal council, it was then that the previously subtle

representation of political authority seen during the Big House Ceremonies

became blatantly obvious.

CONCLUSION

The

Delaware Big House functioned semiotically and symbolically on three levels:

conception, construction, and use. The Delaware Big House existed first in myth.

There are many examples of mythic architecture that remained bound within

language. Streets of gold, castles in the air, and emerald cities can serve

symbolic functions without ever having to be built. The Delaware Big House,

acted out an entire level of encoded messages before a branch was cut.

When

the Big House was transformed from myth into reality, it could have been framed

solely by its symbolic imagery and viewed passively as a work of sculpture, such

as in the case of the shrine or memorial. But it was more than a shrine or three

dimensional piece of sculpture, it was a machine that stimulated and

accommodated symbolic interaction. As such, it became reinterpreted, along with

the sights, sounds, smells, jesters, costumes, and narratives of the ceremony

back into imagination through experience.

The

Big House naturally fit into the symbolic concepts within the Delawares' world

view. The Big House brought the Delawares' symbolically created social,

political, and religious worlds together, to function in unison. This concert of

symbolism, made visible the world and life of the Delawares.

Notes

1 The exact age of the Big House

Ceremony is unknown. The descriptions which follow are summarized from sources

dating between the late nineteenth century and lasting until the 1920's.

2

Babcock, Barbara. Reflexivity. In The Encyclopedia of Religion, ed.

M. Eliade, vol.12, pp. 234-238. New York: Macmillan, 1984.

3

Sullivan, Lawrence E., ed.,

Native

American Religions: North America.

New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1987.

4.

Bogatyrev, Peter. "Costume as a Sign." in Semiotics of Art: Prague School

Contributions, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1976, p. 14.

5

C. A. Weslager.

The Delaware

Indians: A History. New Jersey:

Rutgers University Press, 1972, p.492.

6 Goffman, Erving,

Boston Frame Analysis: An Essay on the

Organization of Experiencen3:

Northeastern University Press,1974.

7

Nabokov, Peter and Robert Easton. Native American Architecture. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 88.

8 Nabokov and Easton.

Architecture.

p. 17.

9 Nabokov. Architecture,

pp. 16- 40.

10

Nabokov. Architecture,

p. 38.

11 Goddard, Ives. "Delaware." in

the

Handbook of North

American Indian., Vol.15,

Northeast, Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978, pp. 229-230.

12 Preziosi, Donald.

The Semiotics of the Built Environment: An

Introduction to Architectonic Analysis.,

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979, p.63.

13 Nabokov.

Architecture., p. 38.

14 Newcomb, William W. Jr. "The

Culture and Acculturation of the Delaware Indians",

Anthropological Papers.

No. 10, Museum of Anthropology, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1956.

15 Newcomb.

Culture,

p. 65.

17. Bleeker. Delaware Indians. p.103.

18.

Bleeker. The

Delaware. p.116.

Delaware Street Rag by

Michael Caron

First Song: XENGWIKÁON [A Story]

Verse VII: Big House

The most controversial element of Mary's [Mary Zeigler's] unorthodox

historical geography was her contention that the Lenape Big House, the

Xengwikáon, came into existence at the time of contact with Finns. The

Xengwikáon was the most important ceremonial structure of the Lenape

people. It was, as the English translation implies, a very large

ceremonial house. It was made of notched logs. The Big House was a

double log cabin with two openings in the roof. Few Lenape have ever

claimed the log version of the Big House existed before European

contact. Yet Mary discovered there was virtually nothing in the academic

literature or in Lenape oral traditions concerning the origins of the

Big House itself. Lenape mythology did, however, have a lot to say about

the origins of many ceremonial practices, elements of which clearly

dated back into the depths of their cultural memory. This large log

cabin adopted as a religious site was simply dismissed as mere copying

of pioneer log churches. That was about as ludicrous, and as easy to

disprove, as the

notion that Vikings had brought the sweat lodge to America. Mary found

documentation that strongly indicated at least some of the Finns and

Lenape found common ground in their ways of worship. Old colonial

records in Swedish archives, and other evidence in the folklife studies

of Finland, convinced her that the Big House phenomenon represented a

significant transformation of the traditional Lenape belief system to

accomodate the ways their world was being impacted by the coming of the

Euros. The Big House had remained the central focus of most Lenape

spiritual life until well after they moved to Kansas. She argued, much

to the chagrin of many scholars and more than a few Lenape, that many of

the Big House ceremonies had originated in the period when the influence

of the Finns was at its peak. The Big House was the place where

Fenno-Lenape cultural beliefs had blissfully cohabited.

Mary knew that the meeting

of these two peoples had occasioned a major upheaval in both their

lives. That should be obvious to anyone. Yet in most instances these

contacts had resulted in what was undoubtedly one of the most compatible

and mutually beneficial encounters in the history of Indian White

relations. That circumstance alone would have provided ample reason to

rethink and reshape the spiritual content of their lives. The Big House

ceremony, in Mary's eyes at least, was intimately associated with the

adoption of log cabins as the primary Lenape house type. But the log

house was only the symbolic center of a much wider and more profound

shift in both Lenape and Finnish cultural meaning and values. Both

cultures were in a fluid state of profound changes. The new habits and

habitations were intimately linked to modifications in traditional

gardening and hunting habits. Life changed dramatically for the Finns

after they settled among the Lenape. It was only natural that these two

peoples would create a ceremonial center that reflected elements of this

cultural union. It was equally certain that the Finns who had been under

constant pressure to abandon their shamanistic beliefs and practices

would keep this out of view of the Swedish colonial authorities. Mary

says that the firestorm her theory generated was not what she was

expecting. But knowing Mary I suspect she anticipated the outrage and

felt compelled to present her work anyway.

Mary knew that the meeting

of these two peoples had occasioned a major upheaval in both their

lives. That should be obvious to anyone. Yet in most instances these

contacts had resulted in what was undoubtedly one of the most compatible

and mutually beneficial encounters in the history of Indian White

relations. That circumstance alone would have provided ample reason to

rethink and reshape the spiritual content of their lives. The Big House

ceremony, in Mary's eyes at least, was intimately associated with the

adoption of log cabins as the primary Lenape house type. But the log

house was only the symbolic center of a much wider and more profound

shift in both Lenape and Finnish cultural meaning and values. Both

cultures were in a fluid state of profound changes. The new habits and

habitations were intimately linked to modifications in traditional

gardening and hunting habits. Life changed dramatically for the Finns

after they settled among the Lenape. It was only natural that these two

peoples would create a ceremonial center that reflected elements of this

cultural union. It was equally certain that the Finns who had been under

constant pressure to abandon their shamanistic beliefs and practices

would keep this out of view of the Swedish colonial authorities. Mary

says that the firestorm her theory generated was not what she was

expecting. But knowing Mary I suspect she anticipated the outrage and

felt compelled to present her work anyway.

* * *

THE COSMIC SYMBOLISM OF THE DELAWARE (LENAPE) CULTIC

HOUSE

(Frank G. Speck, A Study of the Delaware Indians Big

House Ceremony, Publications of the Pennsylvania Historical

Commission, vol. 2 (Harrisburg, 1931).)

The Big House stands for the Universe; its floor, the earth; its four

walls, the four quarters; its vault, the sky dome, atop which resides the

Creator in his indefinable supremacy. To use Delaware expressions, the Big

House being the universe, the centre post is the staff of the Great Spirit

with its foot upon the earth, its pinnacle reaching to the hand of the

Supreme Deity. The floor of the Big House is the flatness of the earth

upon which sit the three grouped divisions of mankind, the human social

groupings in their appropriate places; the eastern door is the point of

sunrise where the. day begins and at the same time the symbol of

termination; the north and south walls assume the meaning of respective

horizons; the roof of the temple is the visible sky vault. The ground

beneath the Big House is the realm of the underworld while above the roof

lie the extended planes or levels, twelve in number, stretched upward to

the abode of the 'Great Spirit, even the Creator,' as Delaware form puts

it. Here we might speak of the carved face images. . . . the

representations on the centre pole being the visible symbols of the

Supreme Power, those on the upright posts, three on the north wall and

three on the south wall, the manitu of these respective zones; those on

the eastern and western door posts, those of the east and west. . . . But

the most engrossing allegory of all stands forth in the concept of the

White Path, the symbol of the transit of life, which is met in the oval,

hard-trodden dancing path outlined on the floor of the Big House, from the

east door passing to the right down the north side past the second fire to

the west door and doubling back on the south side of the edifice around

the eastern fire to its beginning. This is the path of life down which man

winds his way to the western door where all ends. Its correspondent

exists, I assume, in the Milky Way, where the passage of the soul after

death continues in the spirit realm. As the dancers in the Big House

ceremony wend their stately passage following the course of the White Path

they 'push something along,' meaning existence, with their rhythmic tread.

Not only the passage of life, but the journey of the soul after death is

symbolically figured in the ceremony.

* * *

The Creator, the Big House, and Lenape Spirituality

(By Toni L. Nuosce, Student, Kent State University Stark Campus November

1998)

Imagine if you can a world

sanctified and respected on a daily basis, in fact imagine that we all

believed that the Earth is our true Mother. To go even a step further,

imagine believing that there is no separation between people and the land

upon which they lived. Wouldn’t we try like mad to keep "her" safe and

away from harm? Wouldn’t we praise our Mother Earth and her creator by

believing every little thing that has been created should be loved and

handled as if it were a newborn child? The Lenape tribes believe this and

their religion is based on the Creator, the giver of all land. Because the

Lenape’s are a very gracious people, they built their temple, the Big

House, to express their gratitudes and spiritual visions.

The Lenape’s, or "True Men", believe

they are created from the earth and pay their respects and deep loyalties

to it’s Creator. An established American Indian author Hitakonanulaxk, of

the book The Grandfathers Speak, describes his people best by

expressing a popular saying they recite, "We do not own the land, we are

of the land, we belong to it" (Hitakonanulaxk 2). With this extraordinary

attitude comes the building of the Big House. The Big House for the

Lenapes would be like a church for the Christians, or for the Jews a

synagogue, yet by any means it is a place to worship and give thanks for

all they possess, materially and spiritually.

The Big House’s structure is extremely

and thoughtfully symbolic. This is not simply four walls, a dirt floor,

and a roof where people come to worship, everything has meaning. Only

materials from Mother Nature are used in the construction of this highly

symbolic place of worship. Robert S. Grumet’s, The Lenapes,

detailed description of the Big House makes it’s symbolism visual, "The

floor was the earth. The roof represented the heavens. The central post,

decorated with carvings of Mesingw, is a vertical shaft connecting the

earth with the upper and lower worlds (Grumet 77 & 78). Mesingw is a

series of twelve carvings believed to be the deliverers of prayer to the

Creator.

The number twelve is also symbolic,

because of the belief that the Creator dwells in the twelfth heaven, the

highest heaven above the Earth. Due to the significance of the number

twelve, the ceremonies in The Big House last twelve days. During these

twelve days the Lenapes give thanks and praise to the Creator. Frank G.

Speck, author of, Oklahoma Delaware Ceremonies, Feasts, and

Dances, enlightens us with a clear description of the Lenape’s need

for creating the Big House, "The infallible Father and Creator seated in

the twelfth heaven above, in his beneficence toward man is believed to

yearn for the voiced recognition of his creatures as they pay their

devoirs to him - his human children gathered to celebrate the twelve day

ceremony of the Big House" (Speck 154). They believe that the Creator

desires to hear their praises and they, being devoted to the Creator and

the ceremonies in the Big House, without hesitation offer "him" a special

place where they pay homage to the Creator for everything he provides

them.

The need for the Big House as a

sanctuary to praise the Creator is of extreme importance to the Lenapes

because they feel one with the earth and believe it necessary to respect

all inhabitants and creations. They believe that paying their respects to

the Creator in this holy place will bring them the essentials they need

for daily living. The Creator provides them with the bare necessities in

life, such as animals for food, rivers for drink, and air to breathe in

order to maintain life. Due to the these facts comes the symbolic

structure of the Big House, by virtue of design, the Big House is not

looked upon as a physical structure but a representation of the universe.

The Lenapes are a strong people

connected to the earth, seas, heavens, and winds. For all of their

spiritual guidance they receive from Mother Earth and the Creator, they

believe in praising them for all that they offer. I would like to close

with a beautiful quote from a true Native American Indian, Hitakonanulaxk.

Hitakonanulaxk speaks a final thought

that will hopefully create a lasting impression on Lenape spirituality,

"Our Creator, he made no mistakes. It is not much different than if one

considers the heart being where it is in the body and not in the head

where the brain is. The heart is where it is for a reason, and this can

also be said of a people. The function of the heart in the body is

analogous to the religion and ceremonies of a people. Our spirituality,

our religion, is our heartbeat, and our culture and traditions, our life’s

blood" ( 3 ).

From:

Oklahoma

Archeological Survey 111 E. Chesapeake Norman OK 73019-5111 (405)325-7211

Contact Webmaster: archsurvey@ou.edu

Times New Roman 12 point. Copy 15 December 2004.

Photo check A. TH

More

Links: